Violin Scales: Learn the Most Common Scales on the Violin

Violin scales with free sheet music, finger charts and audio samples

Practicing scales on the violin is very important to:

- learn to play in tune (improve intonation)

- practice different bowing techniques

- improve your rhythm skills

- finger speed, flexibility and strength

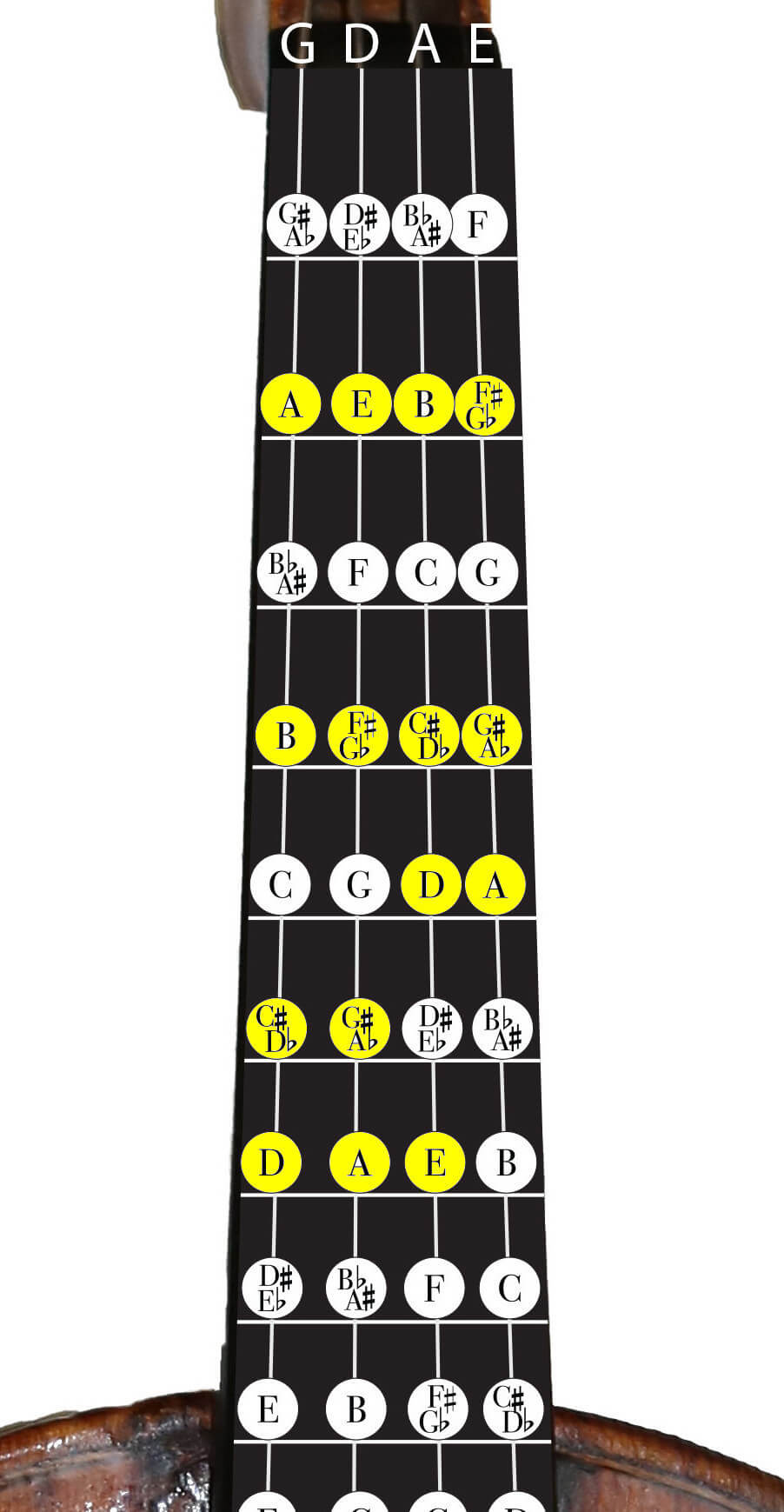

Actually there’s nothing you can NOT learn with scales. You get to know the violin fingerboard, where all the notes are and in general scales are a laboratory to improve all aspects of your violin playing.

If you start each practicing with scales, you’ll notice that your overall violin technique improves and you can learn all the piece you love to play faster and better.

I’ll dive right into the most commonly used violin scales. General information about what a scale is and how to practice them comes later in this article. Just scroll and jump to what you’d like to learn first.

A Major Violin Scale

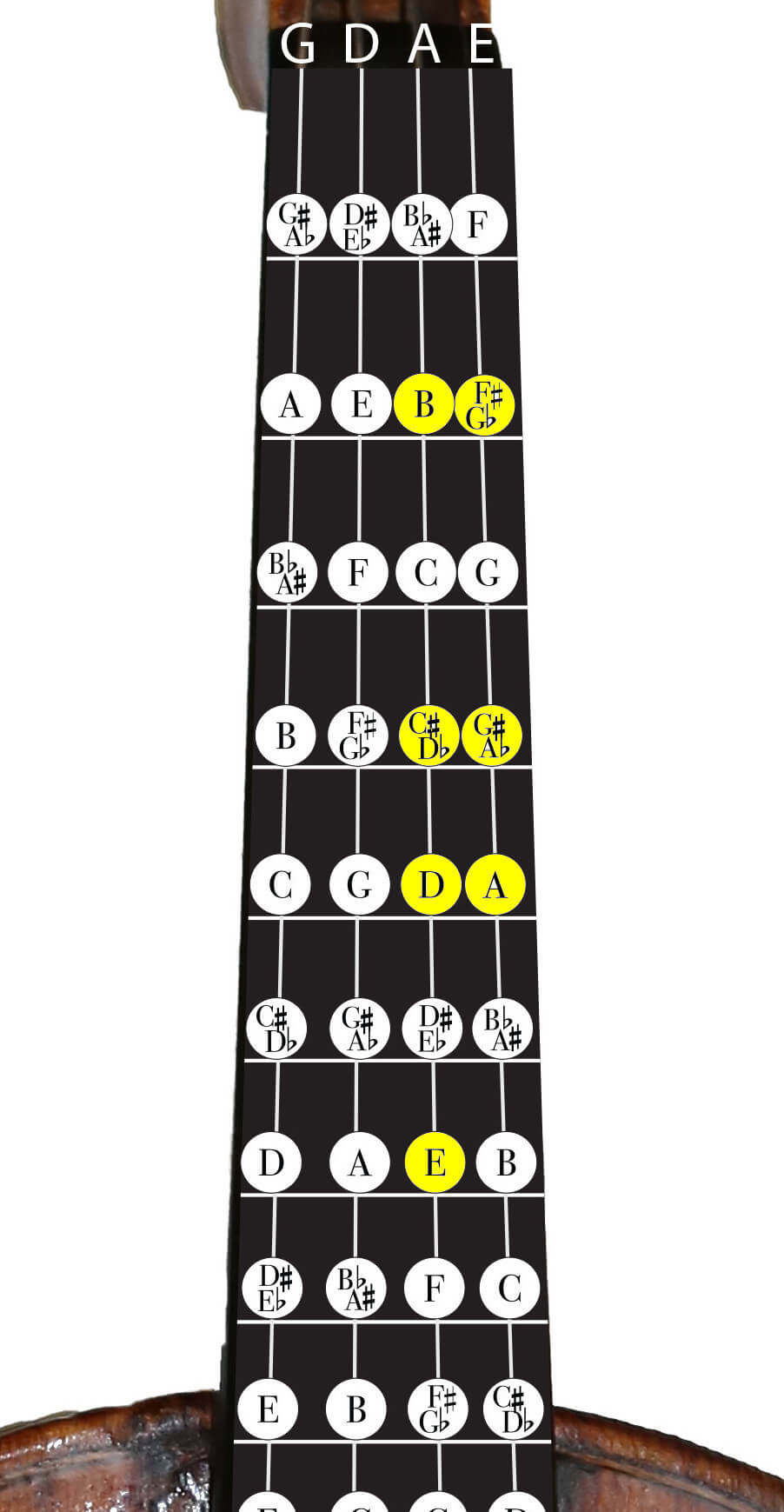

This is the first scale almost all violinists learn and a very comfortable key to play in. It has three sharps, F#, C#, and G#.

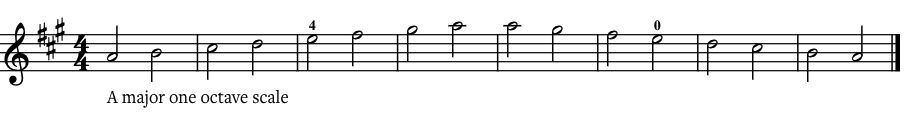

Beginner A Major One Octave Violin Scale

(Sensational Scales p. 2-4)

Start on open A. The fingering pattern is easy here because you just have to follow the tapes if you have them. If you don’t have tapes, make sure your high second finger always touches third finger. For the E, you can choose whether to play four on the A string or open E string.

Sensational Scales includes exercises in broken triads. These are the exact same notes and fingerings, just in a different order. Start on A, skip up to C#, come back down one step to B, skip up again, etc.

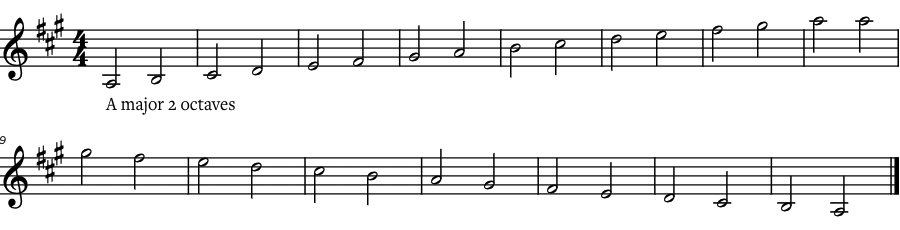

Intermediate A Major Two Octave Violin Scale

(Sensational Scales p. 16-17)

Here we add the lower octave on the G and D strings. Start on 1st finger G string. The fingering is pretty simple, just make sure to play high 3’s on the G and D strings. Everything else is the same, no shifting is necessary. Also try the bowing variations given in the book.

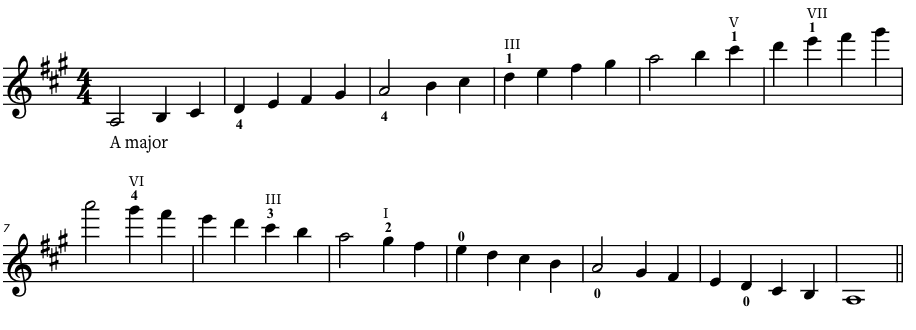

Advanced A Major Three Octave Violin Scale

(Sensational Scales p. 58,71)

This advanced scale requires shifting up to third, fifth, and seventh position. For most accurate results, always slide the shift carefully, never jump or jerk. The book gives two different options for fingerings. The Carl Flesch fingering is the most common. Experiment with both to become a flexible player.

The arpeggios here cycle through both A major and A minor.

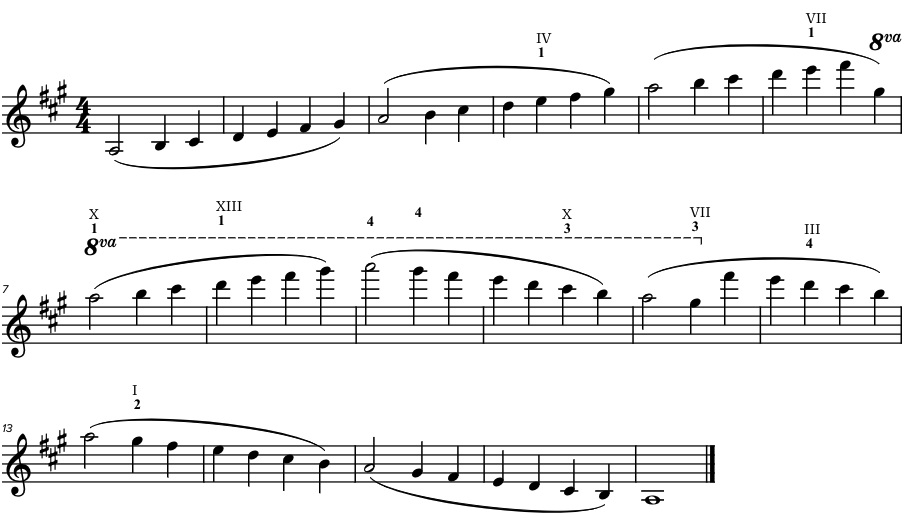

Pro A Major Four Octave Violin Scale

(Sensational Scales p. 79)

A Major is one of the few scales that violinists can actually play in four octaves. That last A is one of the highest notes on the violin. Four octave scales don’t come up in sheet music very often, but examples in A major are the opening of Paganini Caprice No. 5 and the last few lines of Saint-Saëns Introduction and Rondo Capriccioso. If you hope to play this repertoire someday, brushing up on your four-octave scales would be a good idea.

Fingering-wise, once you get to third position A on the E string, just keep going up 1-2-1-2 until you get to the D in 13th position. Play the last five notes 1-2-3-4-extended 4 for the last A. Bring the four back to G. After that, it’s just 3-2-1 shifts all the way down the E string.

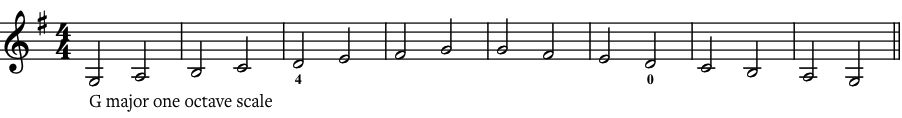

G Major Violin Scale

G major has one sharp, F#. It is the second key most violinists learn to use.

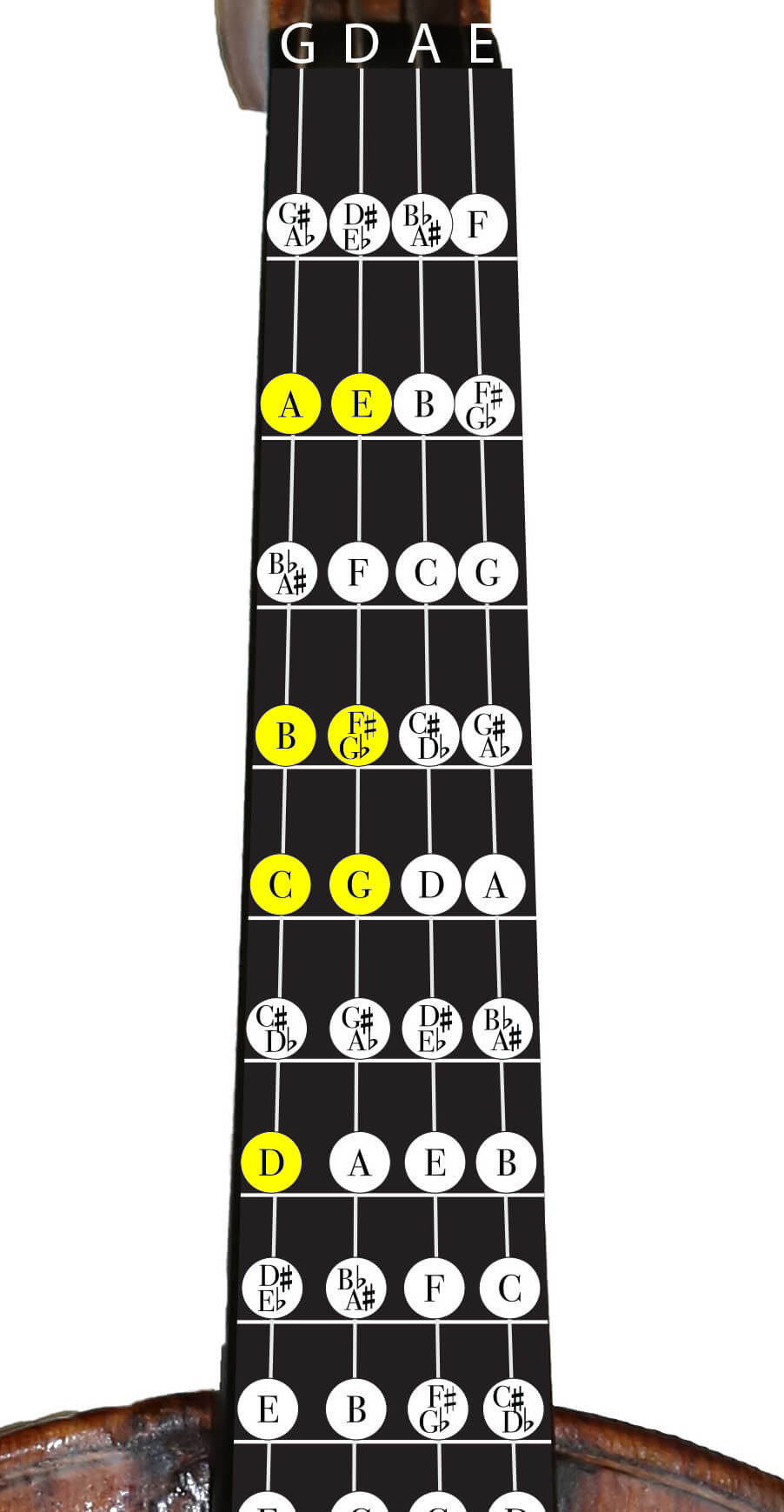

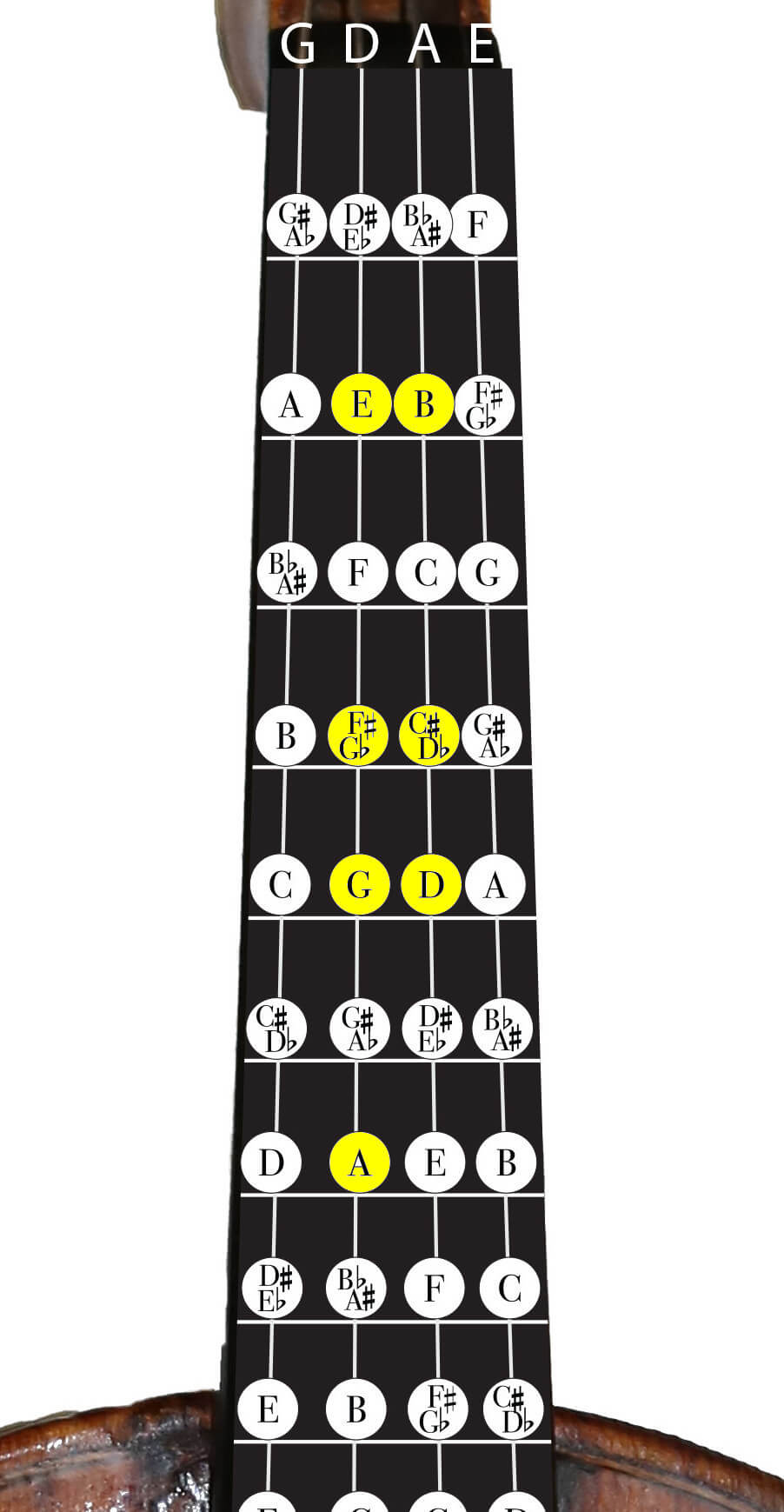

Beginner G Major One Octave Violin Scale

(Sensational Scales p. 2-4)

This scale starts on open G, the lowest note on the violin, and goes up to 3rd finger D string. Play high 2’s on both strings. You may notice this fingering is exactly the same as A major one octave, just starting on a lower string.

Advanced G Major Three Octave Violin Scale

(Sensational Scales p. 56,79)

G major is the easiest three octave scale since it starts on teh lowest note, so you don’t have to shift very high. Just shift to third position on the A string, then 5th position on the E string, and extend 4 for the top G. When shifting down, go straight from 5th position to 1st position on the E string. Remember to always shift carefully and smoothly.

D Major Violin Scale

D major has two sharps, F# and C#, and is the next easiest scale for beginners.

Beginner D Major One Octave Violin Scale

(Sensational Scales p. 2-4)

This is the exact same fingering pattern as A major and G major, just starting on the open D string.

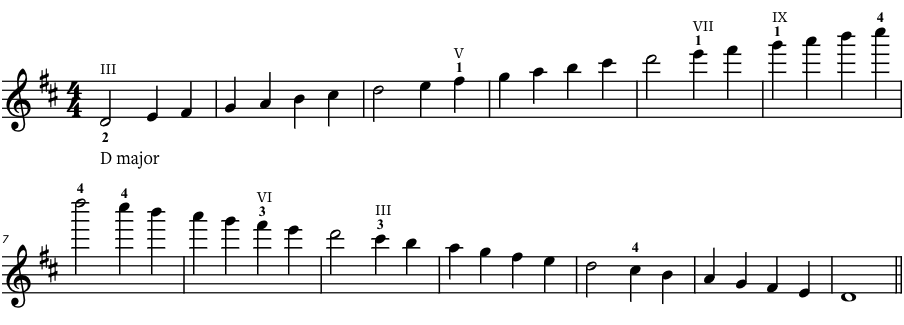

Advanced D Major Three Octave Violin Scale

(Sensational Scales p. 63,76)

G, A♭, and A major all have their own fingerings. However, it is possible to play every other major scale with the exact same fingering, always starting with two on the G string. Then shift once on the A string, twice on the E string, then extended four on the top note. Refer to page 63 of Sensational Scales to understand this. Once you nail this fingering, you will be able to learn different scales much faster.

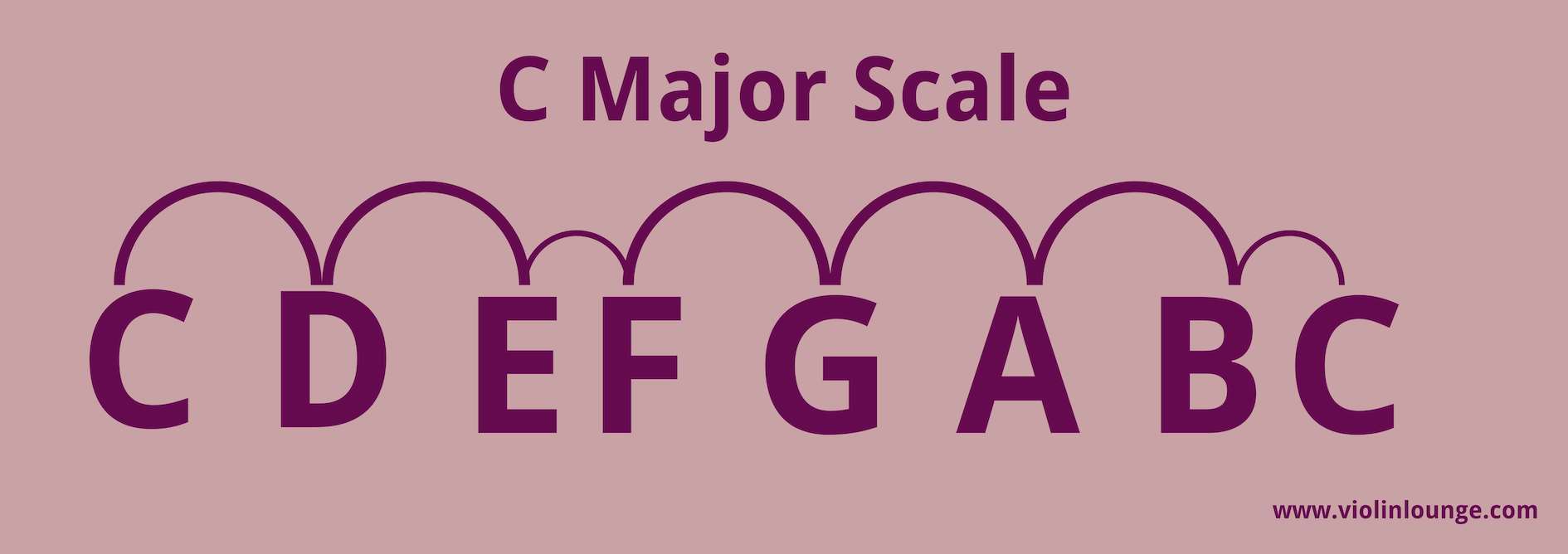

C Major Violin Scale

C major is the major key with no sharps or flats. On the piano you play this key easilly with just the white keys. As the violin is tuned in fifths however, we have different finger frames in this scale and it’s not the easiest scale even thought the key seems easy.

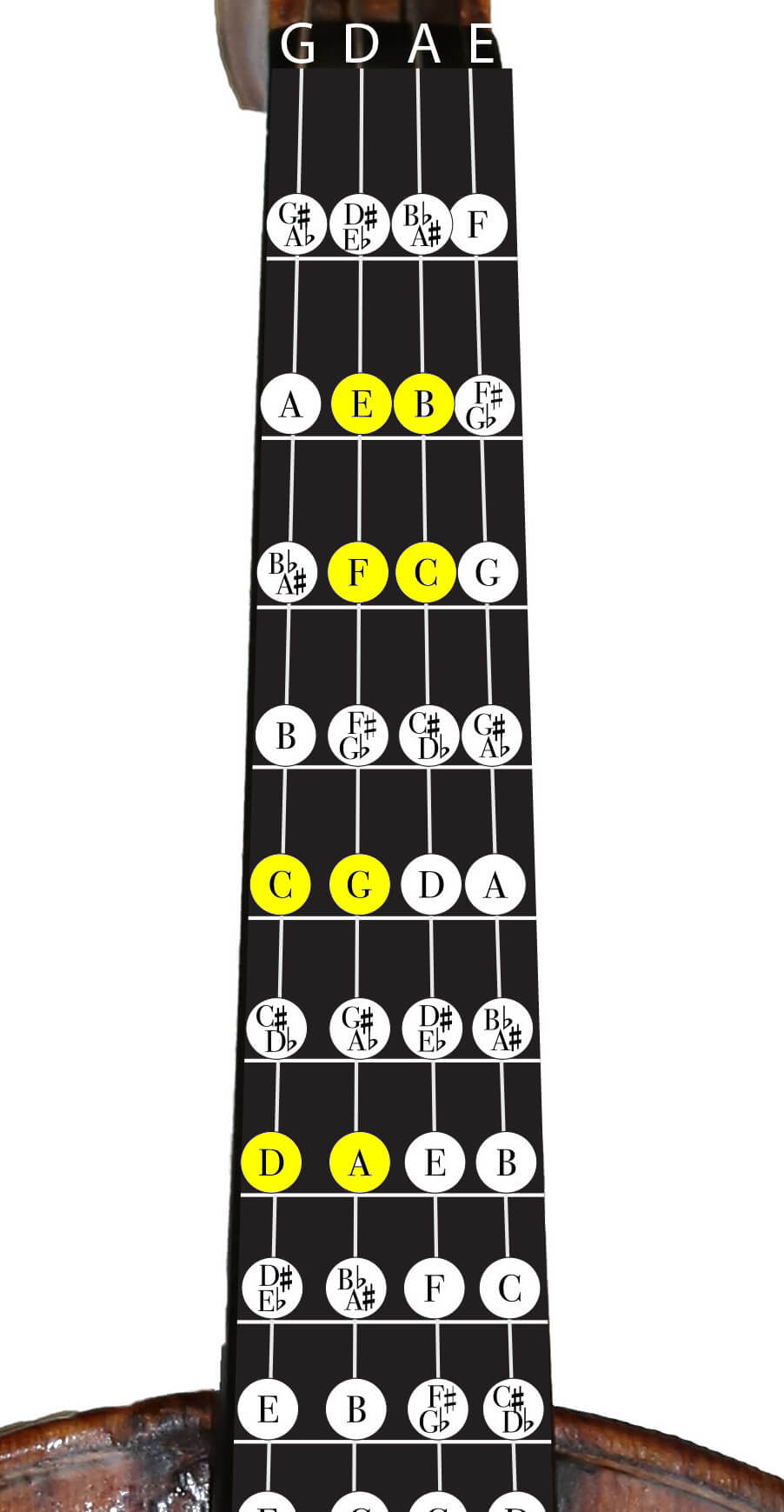

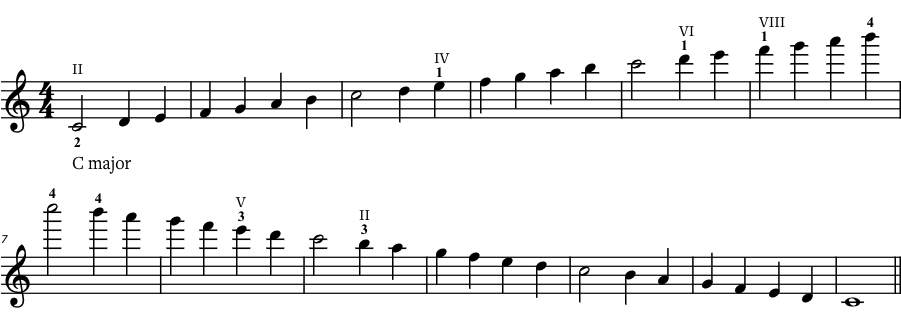

Beginner C Major One Octave Violin Scale

(Sensational Scales p. 5-7)

For this scale, you will need to use low 2nd finger, so make sure your 2nd finger touches your first finger when you put it down. Begin with 3rd finger on the G string, up to low 2nd finger on the A string. This is a really great scale to practice with drones.

Advanced C Major Three Octave Violin Scale

(Sensational Scales p. 61,74)

Use the standard fingering described above for D major. This scale starts in second position.

F Major Violin Scale

This is the only scale on this list that has a flat in the key signature, B♭. This scale is excellent for practicing low 1’s.

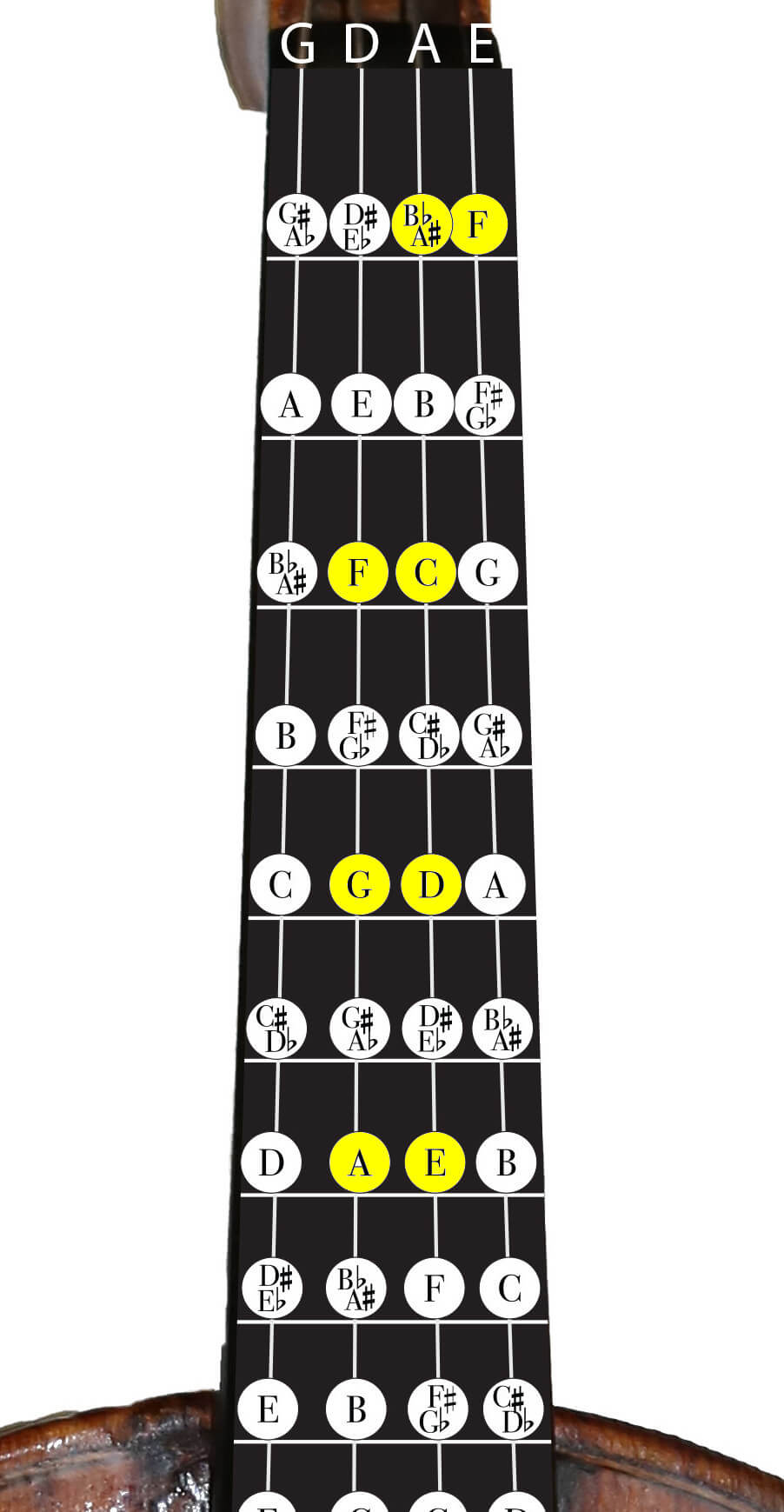

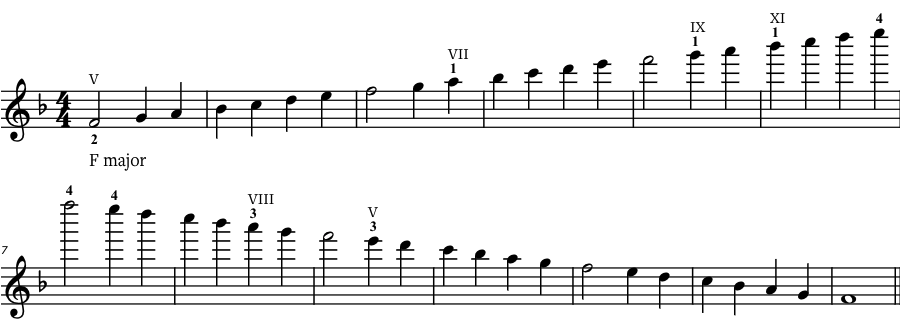

Beginner F Major One Octave Violin Scale

(Sensational Scales p. 12-14)

This scale might seem a bit more challenging at first, but just take it slow. This scale has B and F♮, so all the 1st fingers should be low. Place your finger behind the first-finger tape just a tiny bit above the nut. Use a drone if you have trouble playing those notes in tune.

Advanced F Major Three Octave Violin Scale

(Sensational Scales p. 66)

Here you can still use that standard three-octave fingering, but it starts up in 5th position. This might feel uncomfortable at first, but it’s a great scale for practicing intonation in high positions and really strengthens your fingers. Remember to bang your fingers down to help the notes speak.

FREE Violin Scale Book

All the sheet music you see in this article came from my book Sensational Scales. It’s a 85 page violin scale book that goes from simple beginner scales all the way to all three octave scales and arpeggios.

The beginner scales go together with finger charts, so even if you’re not that comfortable with reading notes, you can follow along.

Unique about this book is that it’s not ordered per key, but per finger frame and level of difficulty. It will take you through all the scales step by step. You know exactly what to do in your violin scale practice.

And the price? It’s FREE!

What is a violin scale?

A musical scale is any set of notes arranged in ascending or descending order. For example, if you want to start a scale on the note C, all the other notes must be played going up or down from C. There is no jumping around or changing directions.

Complete scales, as they are written in exercise books, typically begin and end on the same letter name, but if you look at any sheet music, you will often see little runs of anything from four to twenty-four notes. Although these passages can look intimidating, they are usually based on some sort of scale, so practice scales diligently in order to play these runs with ease.

So if a scale is a set of notes arranged in a particular order, how do we know how close together to put the notes? All western music is built on steps. There are just two kinds, half-steps and whole-steps. If you were to start at the bottom of a piano keyboard and go up playing every single key, you would be playing half-steps. If you count the half-steps between middle C and the C one octave higher, there are 12. (Note: in music we ALWAYS count the first note we play as step 1.) A whole-step is two half-steps put together.

Most scales are a specific combination of half-steps and whole-steps. Although there are many different types of scales, in this article we will only mention the two most common, major and natural minor. The steps of a major scale are WWHWWWH. The steps of a minor scale are WHWWHWW. For example: for the C major scale, start on a C, go up one whole-step to a D, another whole-step to an E, etc. For a C minor scale, go up one whole-step to a D, one half-step to an E♭, one whole-step to an F, and so on. So even though there are twelve steps in an octave, most scales will only use eight of those steps. Let’s look at the steps of the major scale, as that’s the first scale you’ll learn on the violin:

Why Practice Violin Scales?

Good question. Violin-playing is supposed to be fun right? Well the catch is that the better you sound the more fun it is, and the number one way to improve nearly every aspect of your technique is through regular, intentional, and focused scale practice.

When done well, scales can improve tone quality, rhythm, speed, bow control, intonation, shifting, flexibility, articulation, sight-reading… I get excited just thinking about it! If you’re still not convinced, challenge yourself for thirty days to dedicate a specific amount of practice time to scales. Record how your pieces sound both before and after this experience. I promise you won’t be disappointed.

How to Practice Violin Scales?

The main reason most students dread scales is because they don’t have a logical or effective scale practice routine. They don’t know how to use scales to challenge themselves, and therefore end up just repeating the same old exercises and habits for months or years!

If you are focused and make a plan, you will notice your violin scales improving on a daily basis.

Tools that help you practice violin scales

Metronome

The first of course is a metronome. Metronomes are the best goal-setting device musicians have. Start at a manageable tempo, and ramp it up very gradually each time. This is one of the most effective ways to train speed and consistency. Use my free online metronome right here.

Play violin scales with a drone

Another great exercise is practicing scales with a drone playing. The drone can be played either by another (very obliging) musician or a tuner app on your phone. Set the drone to the first note of your scale then play very slowly to check the tuning of every note.

A bit more difficult, but even better, is to play the drone yourself by playing a lower or higher open string along with your scales. I explain more about practicing violin drone scales in this video.

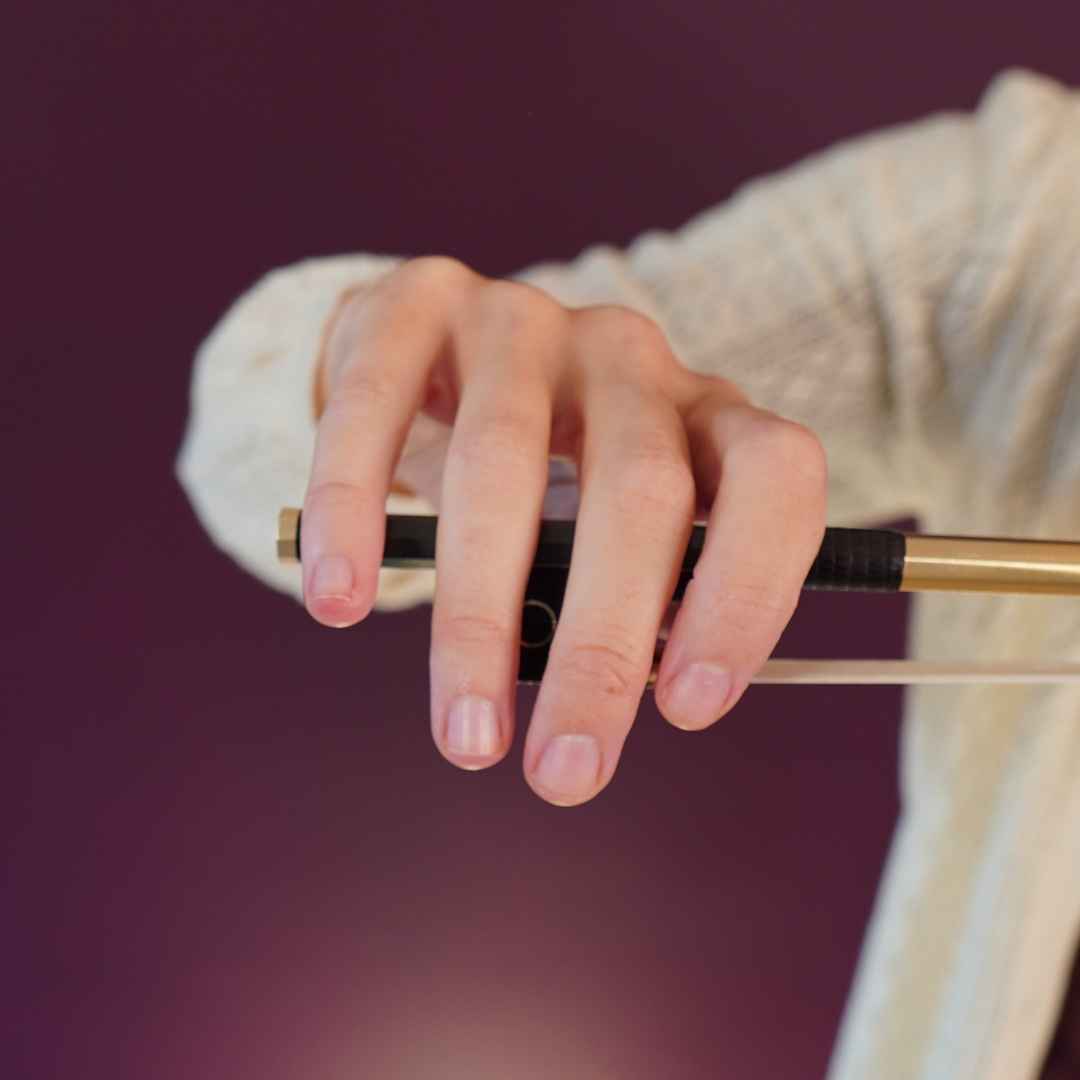

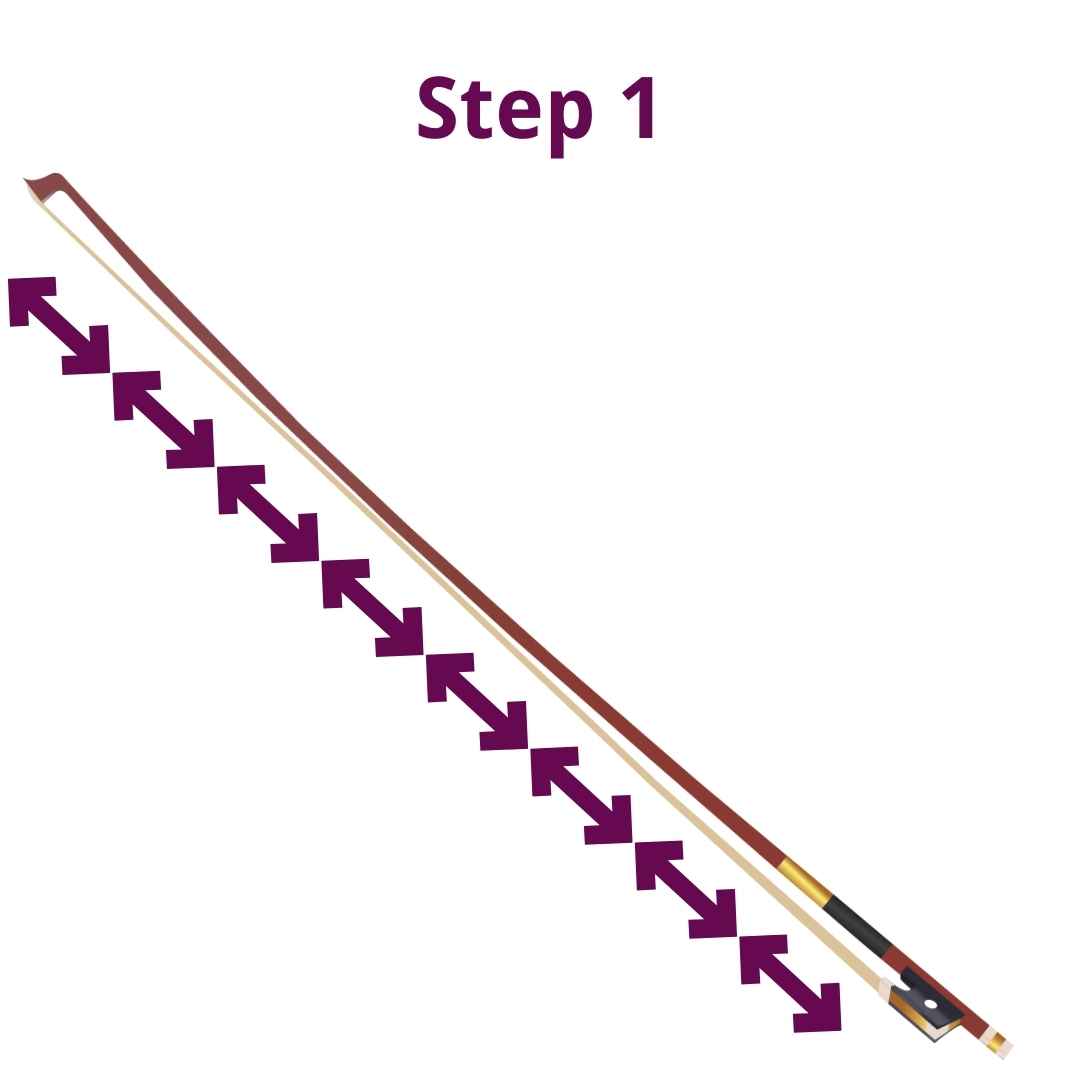

Different bowings

Speed and intonation are the things most people focus on when they play scales, but scales are useful for so many other techniques as well. For example, try practicing scales with increasingly more challenging bowings. The Carl Flesch scale system covers a plethora of advanced bowings, but it’s best to keep it simple and clear first. After mastering one note per bow, try two, then four, then eight, twelve, etc. Continue this pattern (with a metronome!) until you can play the whole scale up and down in one bow. Advanced players often practice doing three-octave scales up and down twice. That’s 84 notes in one bow!

Rhythmical variations

In order to play that many notes so quickly, however, your articulation must be excellent. That’s where practicing with rhythms comes in. Play strong, separate bows and alternate the length of the notes: long short, long short. Make sure the short note is very crisp and clean, shorter than a sixteenth note even. Bang your fingers down (I mean it) on the short notes, and move the bow quickly. Then reverse the pattern: short long, short long. When you put the scale back together normally, your finger dexterity and clarity will have greatly improved.

Bow distribution

The last important thing I’ll address is bow distribution. Many beginners do not think about how much bow they are using for each note. Try to play scales using the entire bow. If you are playing with slurs, make sure to divide the slur exactly in half, meaning if you are slurring eight notes you play four in the top half and four in the bottom half. Practicing bow distribution will help you have a smooth, full tone.

What are arpeggios on the violin?

If you download the Sensational Scales book, you will see that every scale also includes arpeggios. An arpeggio is just a broken chord. For example: the notes of a C major chord are C, E, and G. So to play the C Major arpeggio you would play just those notes up and down the violin. There are many types of arpeggios since you can base them off of any chord.

Chords vs Arpeggios

A chord is when you play several steps (notes) of a scale (for example the first, third and fifth) together at the same time. On a guitar or a piano it’s very common to play chords, but it’s also possible on the violin. Did you know you can play three notes (strings) at the same time on the violin? We call this a triple stop.

On the violin chords are often played ‘broken’. This means you first play the lower two notes together (double stop) and then the two highest notes of the chord or just the highest note.

An arpeggio is when you play the same notes as you would in a chord, but you don’t play them at the same time. You play them one by one, for example: the first note of the scale, then the third and then the fifth. You can play this back and forth.

Chords and arpeggios have the same notes from the scale, but you play them in a different way.

FREE Violin Scale Book

Sensational Scales is a 85 page violin scale book that goes from simple beginner scales with finger charts all the way to all three octave scales and arpeggios

Hi! I'm Zlata

Classical violinist helping you overcome technical struggles and play with feeling by improving your bow technique.

Congratulations on learning the five most useful major scales on violin!

No matter how long you’ve been playing or what level you’re at, improving your scales is the best step to improving your overall violin skills. After learning these five, check out Sensational Scales for comprehensive exercises and explanations of all violin scales.

What’s the best violin scale book?

To practice violin scales, you need a good violin scale book. There are different ones on different levels and with pros and cons.

In this article I describe seven violin scale books, so you can decide what’s the best scale book for you!