Legato Violin Bowing Technique

Legato is the violin bow stroke we use for slurred notes in the sheet music. The transitions between the notes are fluent.

What is legato bowing on the violin?

Legato is the most smooth, flowing way to create sound with the violin. It comes from the Italian tradition of bel canto operatic singing, where the phrase is completely smooth and the notes melt into each other. Legato is notated in sheet music as long slurs over the notes.

Tips for Playing Legato

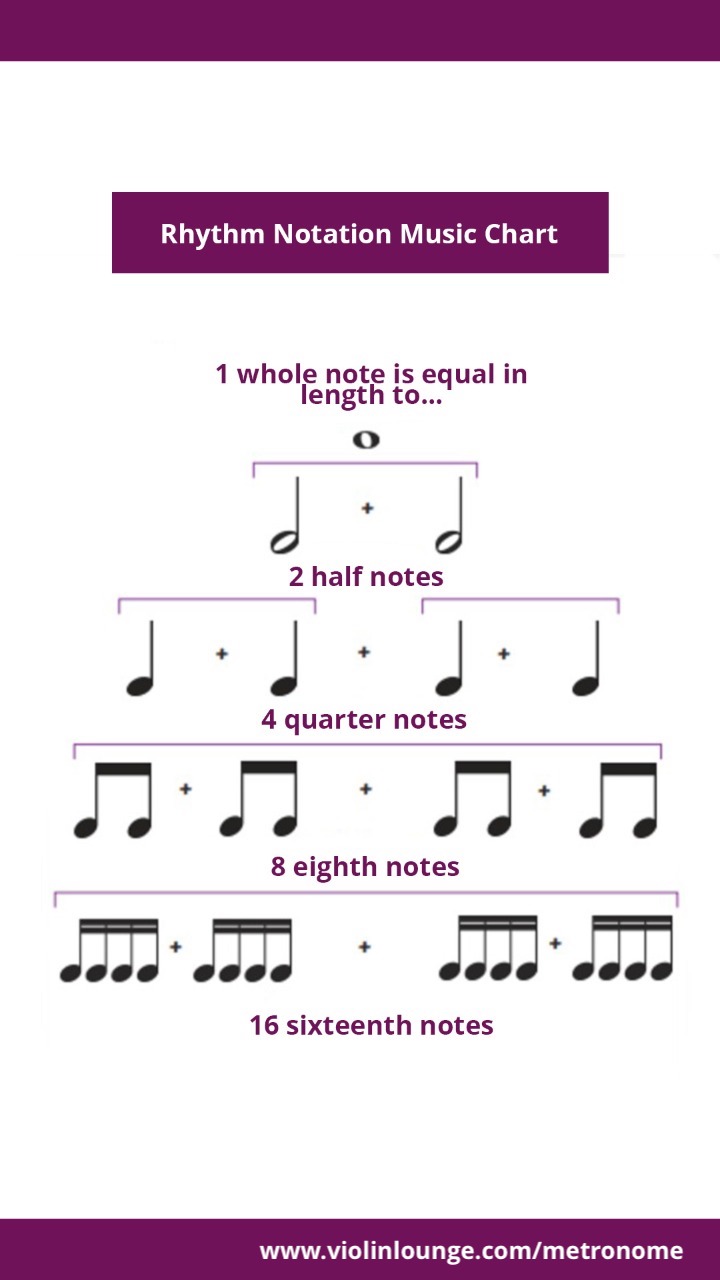

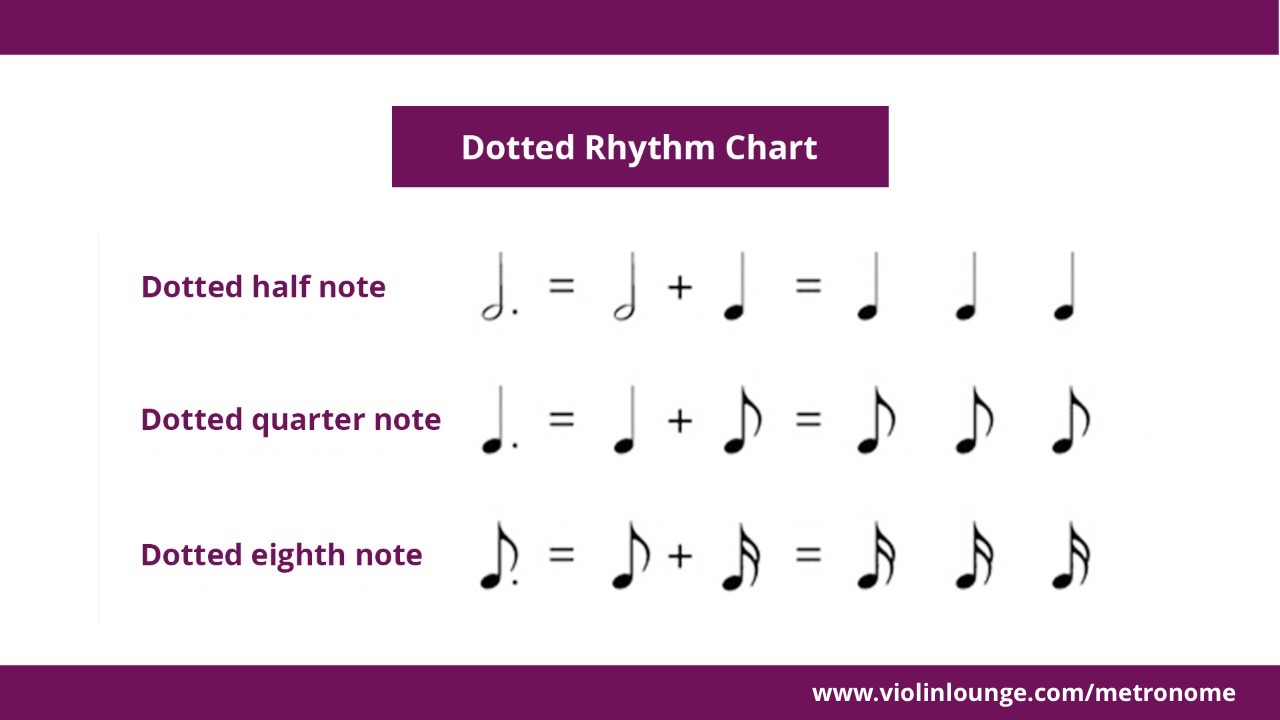

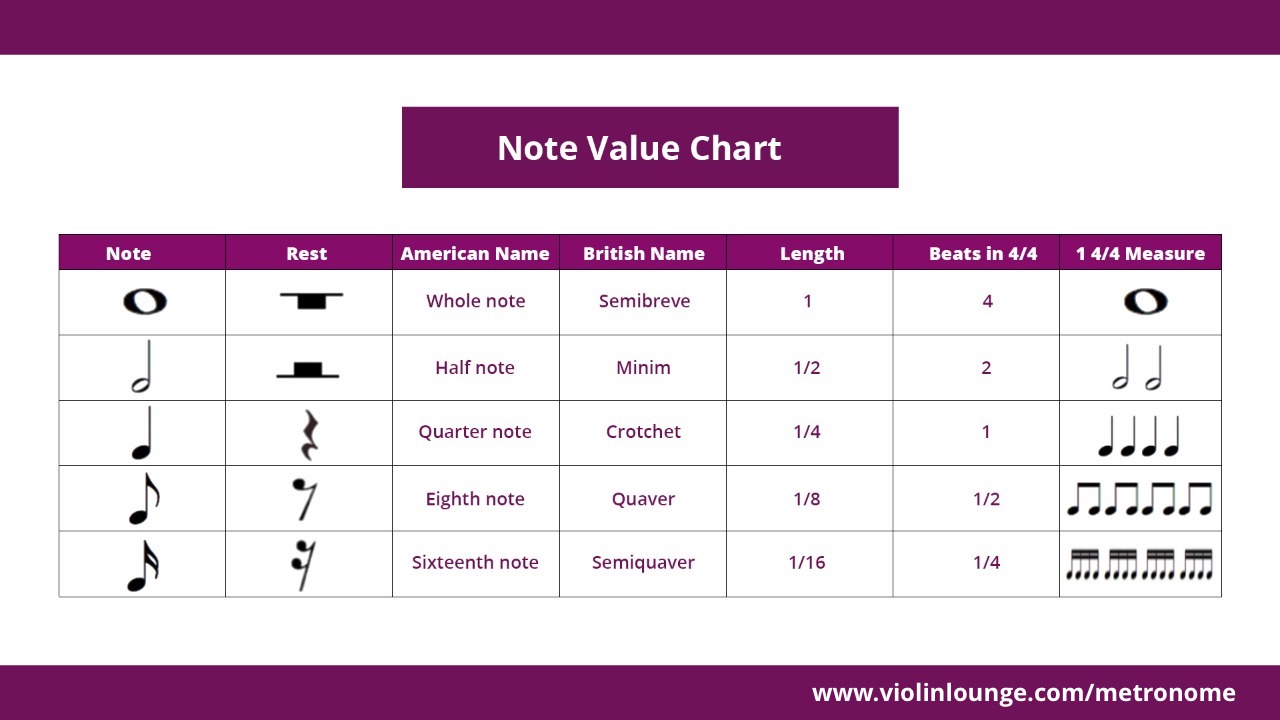

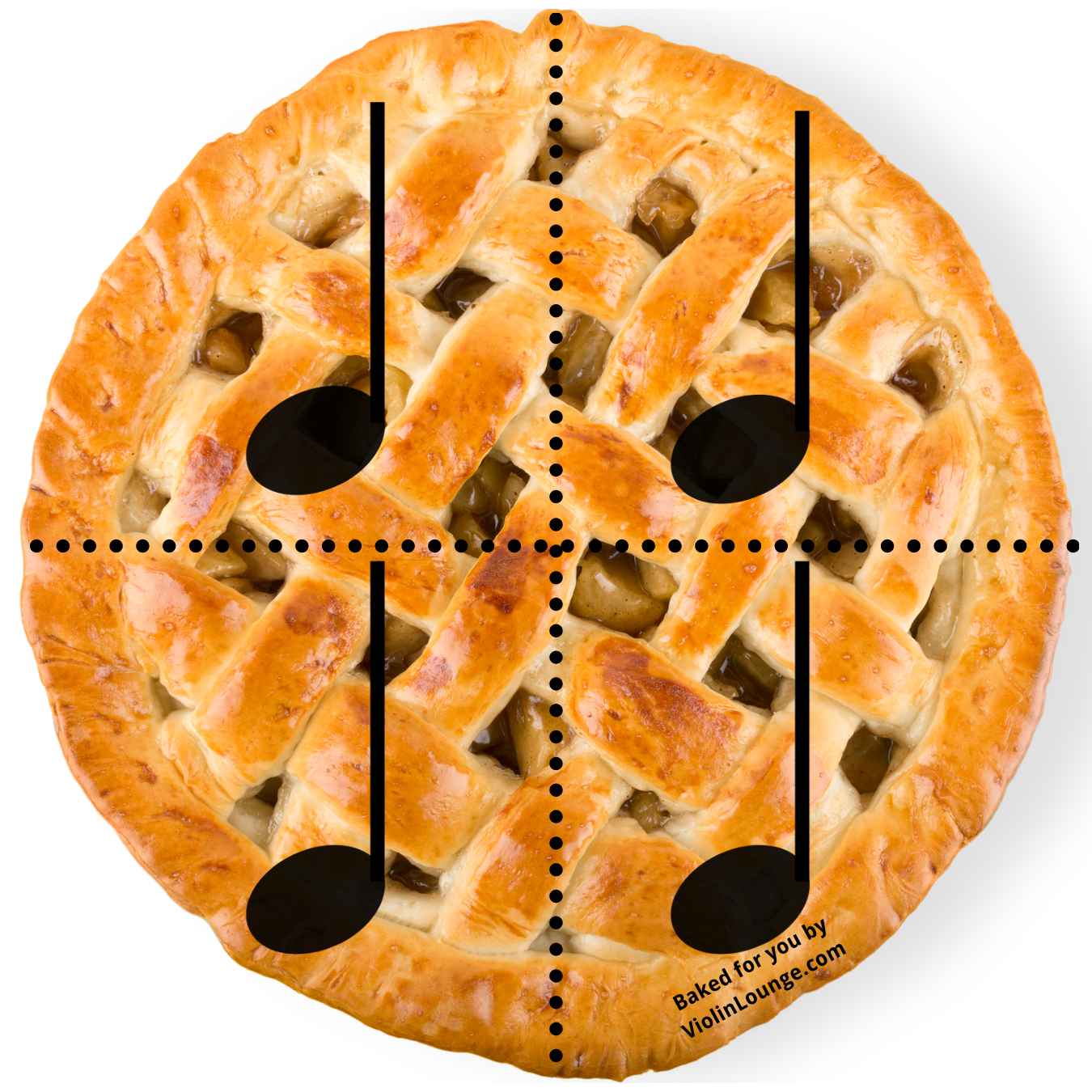

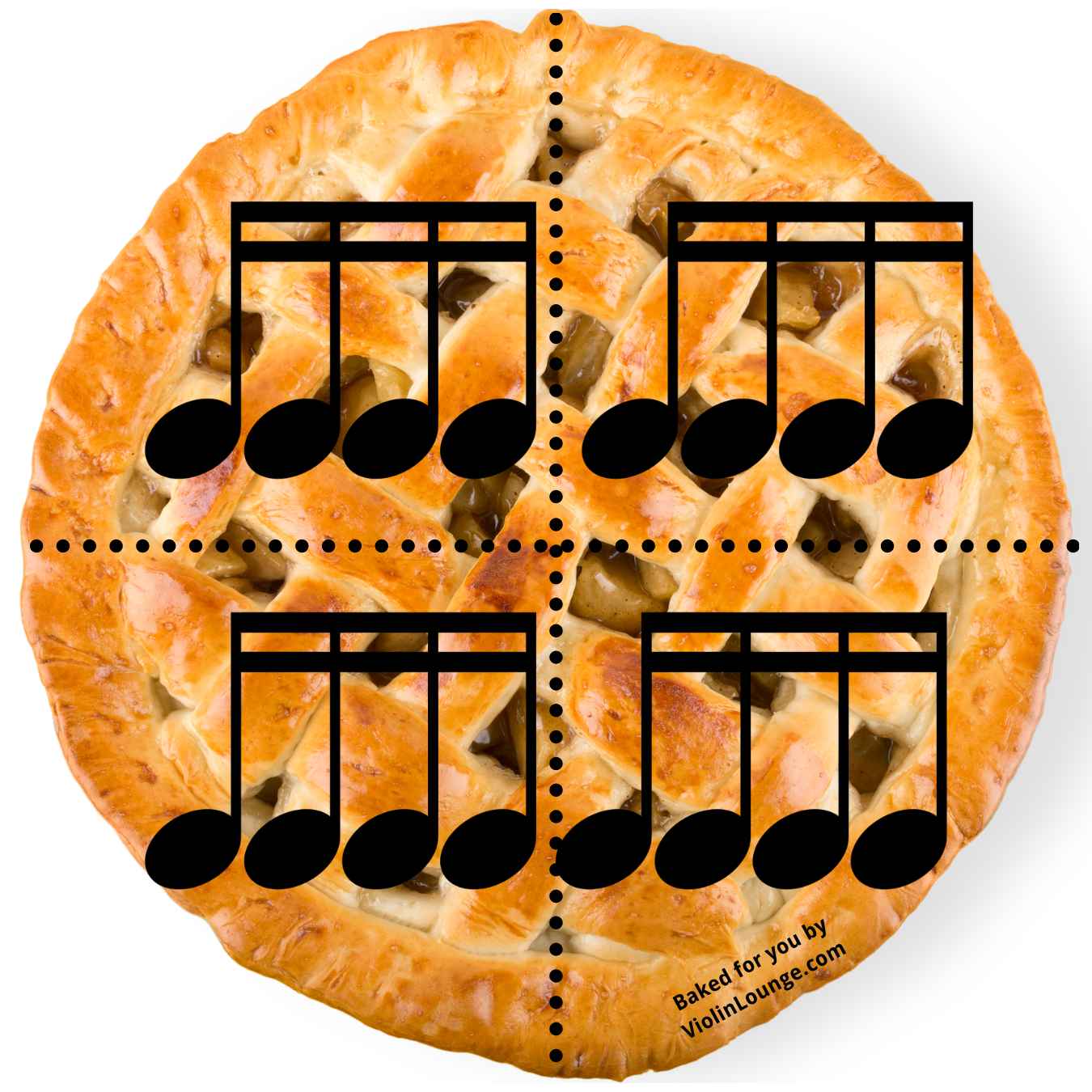

Legato is a difficult technique to really do well, mostly because the hands must work completely independently. Before we get into some exercises for how to do this, let’s go over a few important tips. First, use finger and wrist motion to help create smooth bow changes. As your arm moves the bow across the string, allow your wrist and fingers to move a little further to keep the bow in motion. Ideally, you want no break in the sound. The second important principle is bow distribution. Use an even amount of bow for each note, or each length of note. In other words, if you have eight eighth notes, use ⅛ of your bow for each of them. If you have a half note and then two quarters, use half your bow for the half note and the other half for the quarters. This will help you avoid “belly bowing”, which happens when you increase the pressure just in the middle of the bow. Another good way to avoid this pitfall is practicing in “stop bows”, rearticulating the sound after each note.

To accomplish this, it is tempting to tighten the right hand to create more pressure. Remember that the friction comes from the rosin gripping the string, not your hand gripping the bow!

Independency between the hands means that what you are doing with your left hand does not affect the speed or weight of your bow. How can we develop this? The great violin teacher Ivan Galamian came up with a good exercise: Play two open string whole notes (on the A string for example) followed by two measures of sixteenth notes (finger pattern 0-1-2-0 1-2-3-1 2-3-4-2 etc.) on the same string. Does your right arm feel the same in both versions? How does the left hand impact your smooth bowing? The goal is for the right arm to feel the same on both the open strings and the sixteenth notes. Also, if you are playing fast legato passages with string crossings, putting fingers down early on the next string helps maintain the legato.

Another great legato exercise is called “son file”. The principle is very simple: starting at the frog, play an open string to the tip as slowly as you possibly can, patiently moving your right hand the same speed the entire time.

Legato, Shifting, and Vibrato

You may not have encountered this yet, but legato bowing becomes more complex when you incorporate shifting. Violinists too often create a bump or hiccup with the bow when they shift, especially if they shift too fast. An important key to effortless legato is intentional shifting. The same thing applies to vibrato. Vibrato is not just ketchup that you can throw on top of any technique. It must be clearly incorporated into the articulation. This is again where independency of the hands comes in. The right hand is legato, but the left hand is very crisp and articulate.

Legato Examples in Repertoire

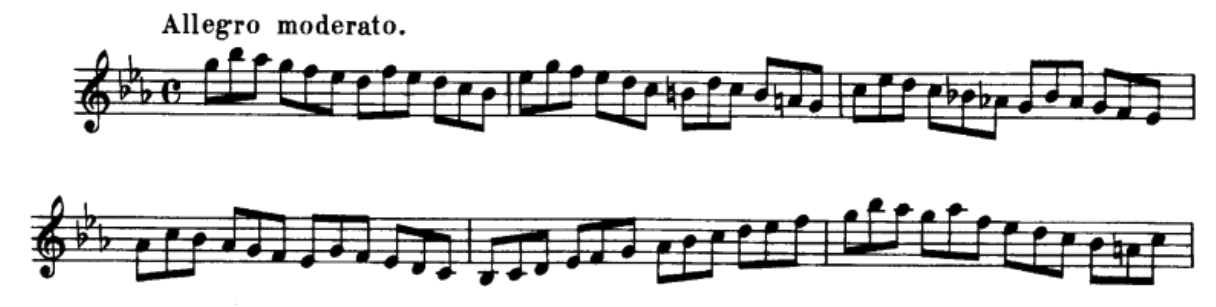

Composers love the expressivity of legato, so it comes up all the time in pieces! You can find a beautiful legato excerpt regardless of your skill level. In fact, one of the most beautiful student violin concertos is also one of the best pieces for practicing legato, particularly the first movement. The melody incorporates quarter, half, and eighth note patterns, an excellent way to learn bow division. The first movement is also entirely in first position.

For intermediate players, I recommend Saint-Saëns’ The Swan. Not only is it one of the most gorgeous and recognizable melodies in classical music, but also a study of how legato, bow control, shifting, and vibrato interact. In this video pay attention to Ray Chen’s bow speed. Notice how he is completely consistent through the slurs, uses the whole bow, and uses faster (but still consistent) bow speed through the crescendos. Notice also how he makes his shifts intentionally audible (portamento) and vibrates before and after each shift for a smooth, luscious sound.

If you’re an advanced player who’s fallen in love with Saint-Saëns and wants a challenge, you can learn Violin Concerto No. 3 in B Minor. Words cannot do justice to the second movement of this piece so please listen to this recording!

Portato or Legato?

You may have noticed that the bow stroke here alternates between legato and a slightly different technique: portato. In portato (also called louré), you stop the bow for a very short moment between the notes. This lovely effect creates variety and build-up in a phrase, for example in the Mendelssohn concerto:

Passages that the composer wants portato are marked with a slur and dashes under the notes. However, portato is also an expressive technique that soloists can choose to incorporate elsewhere. As shown in the Saint-Saens concerto, alternating between legato and portato creates variety and special effects.

Now that you understand how true legato works, try to practice a legato exercise every day. Perhaps this just means taking five minutes to play slow long bows on open strings. Even this simple exercise does wonders for your bow control and legato ability. Legato creates the most expressive violin music, but like every technique it is improved through careful practice.

Hi! I'm Zlata

Classical violinist helping you overcome technical struggles and play with feeling by improving your bow technique.

Improve your violin bowing technique with these lessons and articles:

Do you want to know every possible bowing technique on the violin? Watch this video with 102 violin bowing techniques.

The basis for all bowing techniques is to bow smoothly. This video lesson will help you with that.

A proper and relaxed violin bow hold will help a lot improving your bowing technique and sound. Read this article.

Take bowing technique lessons with Zlata

Join my Violin Bowing Bootcamp to build a great basic technique, make a beautiful sound and learn the most common bow strokes.

Join Bow like a Pro for personal guidance by Zlata and her teacher team combined with an extensive curriculum all things bowing.

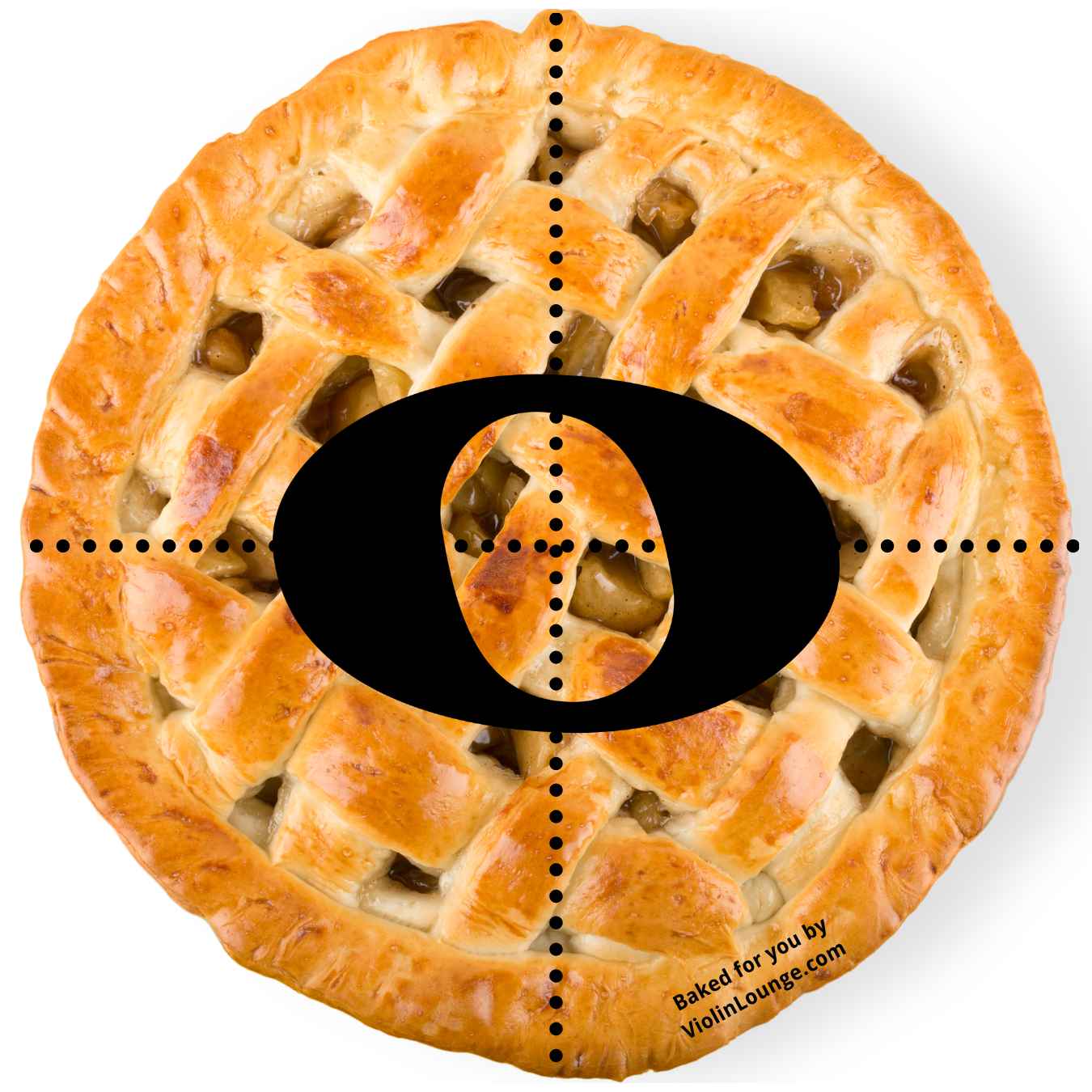

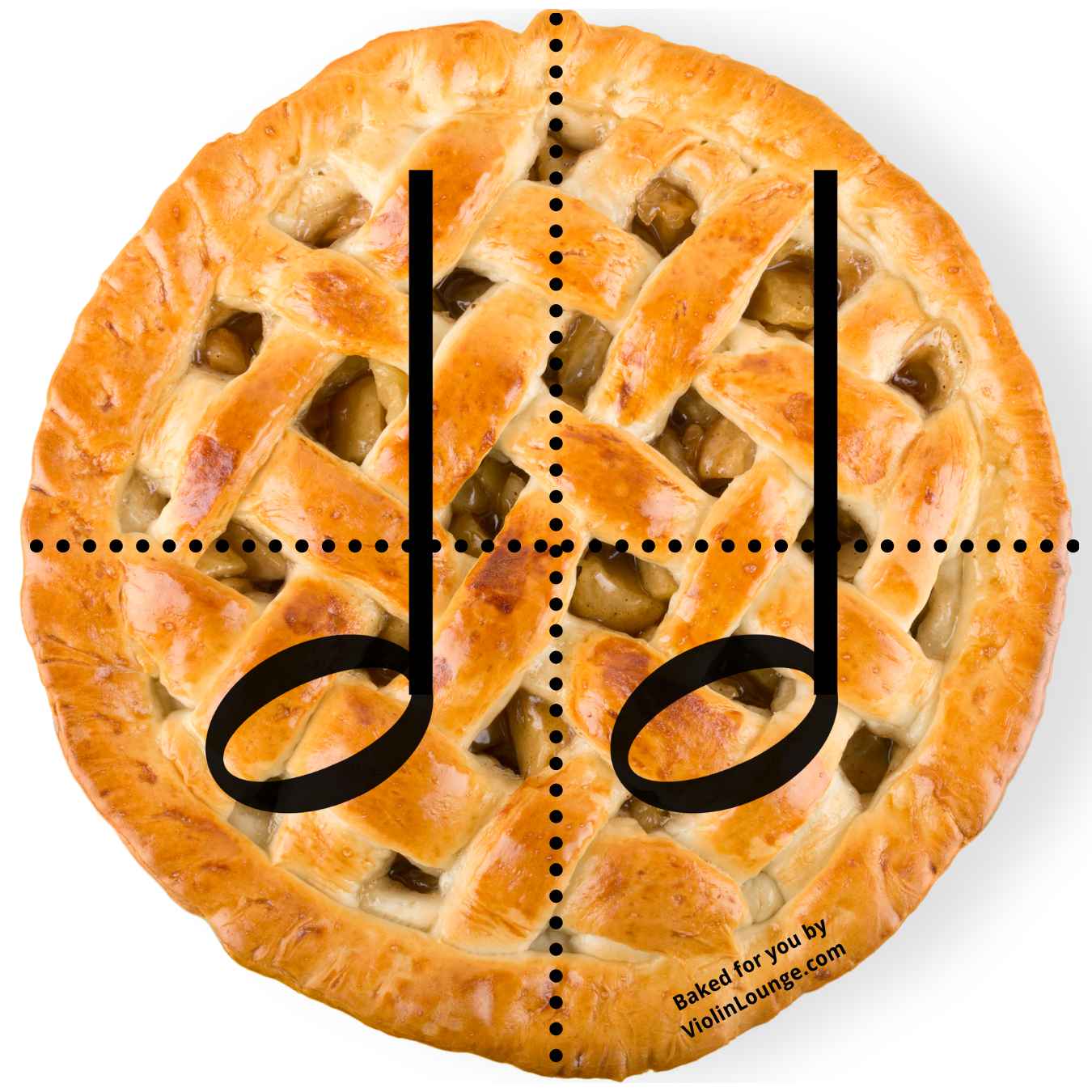

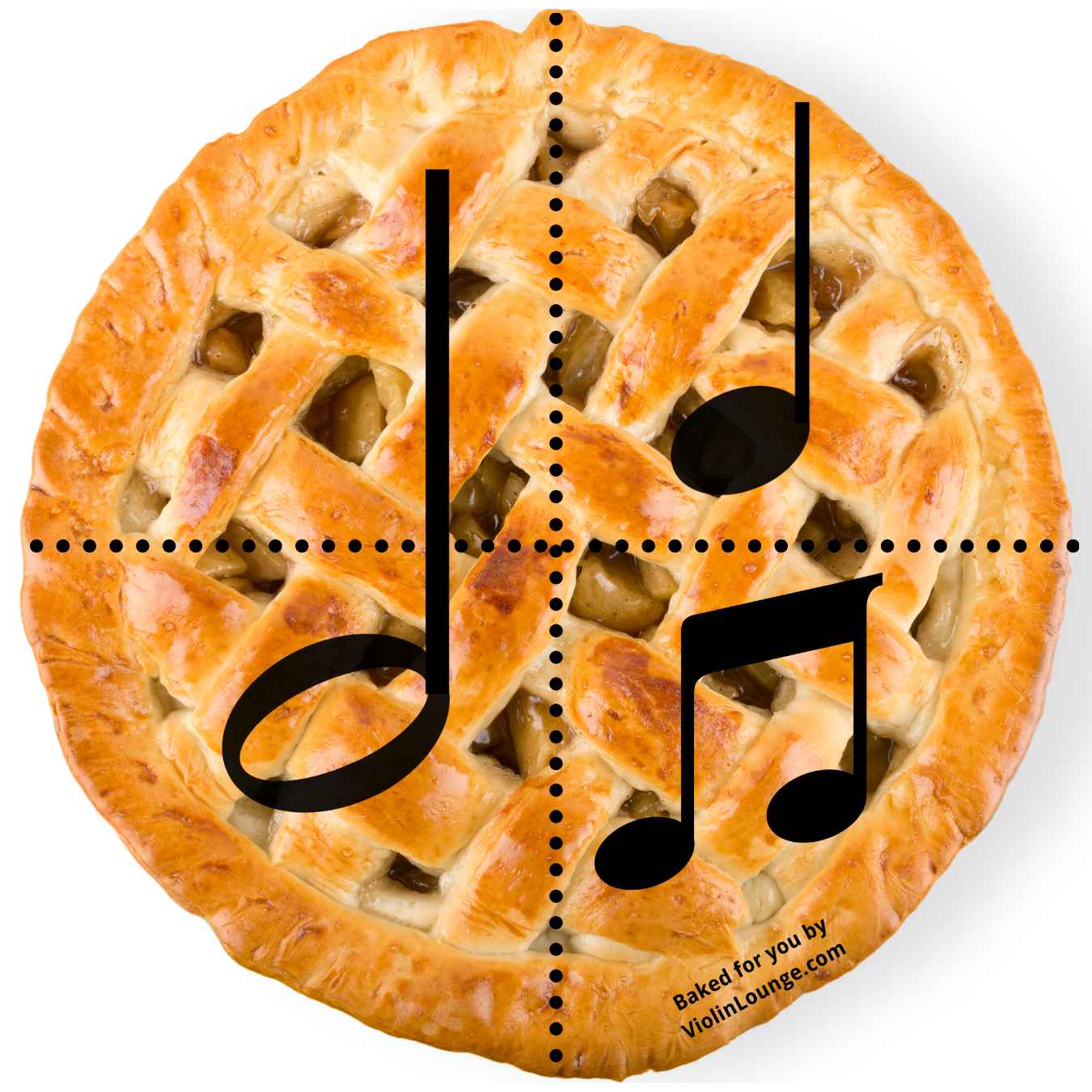

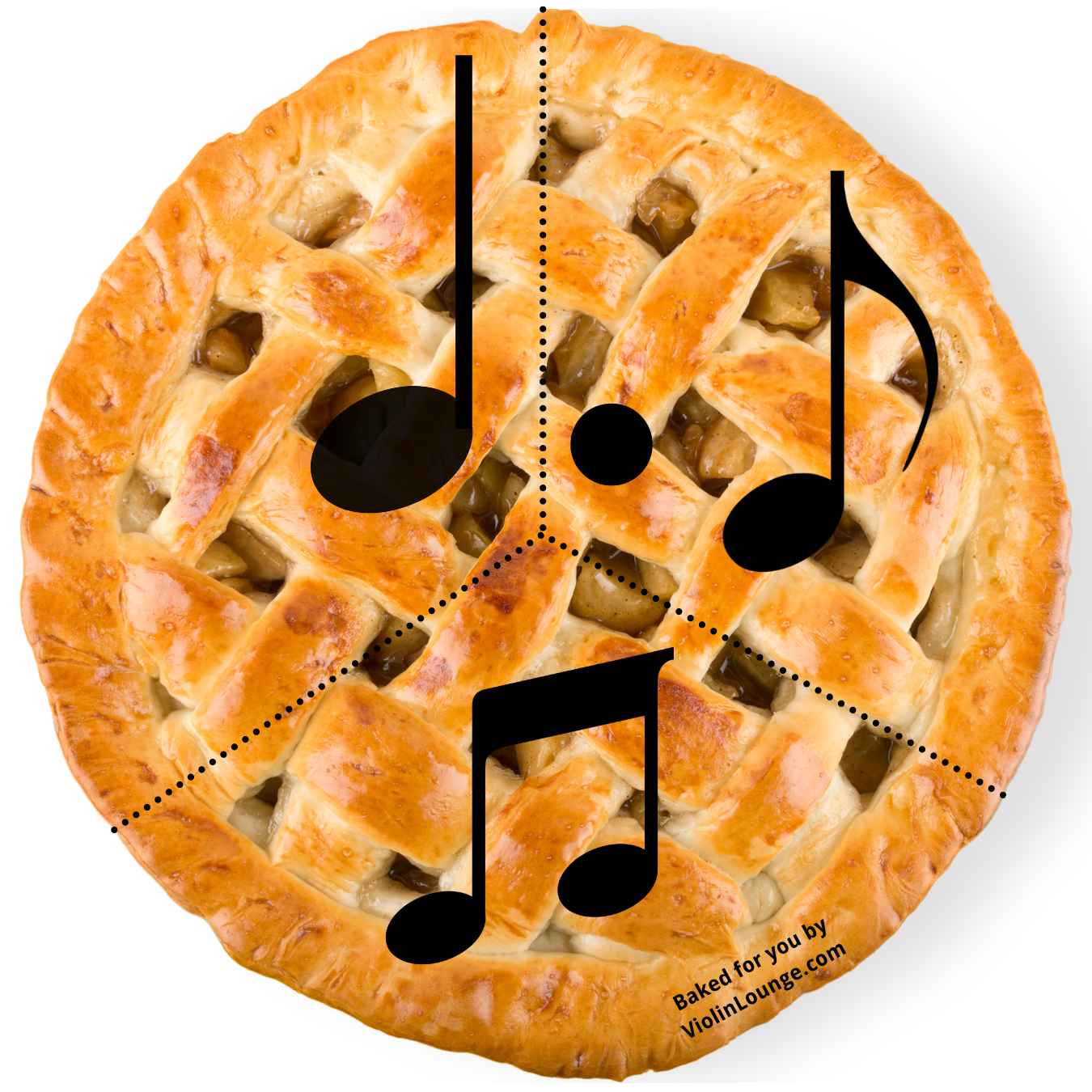

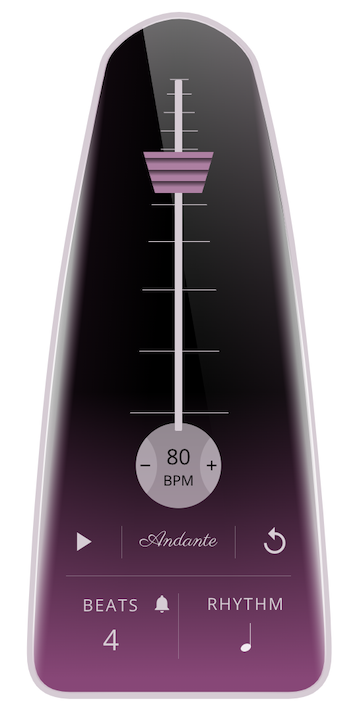

Time signatures are made up of two numbers. The top number indicates how many beats are in each measure and the bottom number indicates which note is equivalent to a beat. For example, in the time signature ¾, the top number 3 tells us there are 3 beats in the measure, and the bottom number 4 tells us the quarter note gets the beat. If you were to see a 2 on the bottom, that indicates the half note gets the beat, an 8 indicates that the eighth note gets the beat, and a 16 indicates that the sixteenth note gets the beat. You can think of the beat as one metronome click.

Time signatures are made up of two numbers. The top number indicates how many beats are in each measure and the bottom number indicates which note is equivalent to a beat. For example, in the time signature ¾, the top number 3 tells us there are 3 beats in the measure, and the bottom number 4 tells us the quarter note gets the beat. If you were to see a 2 on the bottom, that indicates the half note gets the beat, an 8 indicates that the eighth note gets the beat, and a 16 indicates that the sixteenth note gets the beat. You can think of the beat as one metronome click. The standard rhythm is 4/4. If you see a big e in front of the music where the measure usually is, the measure is 4/4. A waltz is usually a 3/4 measure. A tango is often a 2/4 measure.

The standard rhythm is 4/4. If you see a big e in front of the music where the measure usually is, the measure is 4/4. A waltz is usually a 3/4 measure. A tango is often a 2/4 measure.

The tempo marking is most often an Italian term notated at the beginning of the piece. In longer pieces, you may also find that the tempo changes and new tempo markings are given at the beginning of certain sections. Additionally, some pieces may indicate the BPM at the beginning of the piece in which case, you can easily see exactly what speed to use!

The tempo marking is most often an Italian term notated at the beginning of the piece. In longer pieces, you may also find that the tempo changes and new tempo markings are given at the beginning of certain sections. Additionally, some pieces may indicate the BPM at the beginning of the piece in which case, you can easily see exactly what speed to use!

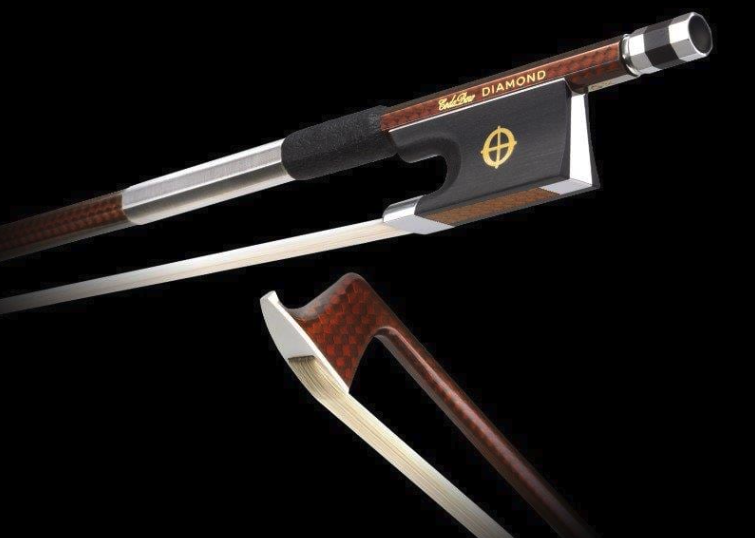

Horsehair is the most traditional and effective material, but we now have the technology to make bow hair out of other things. A company called

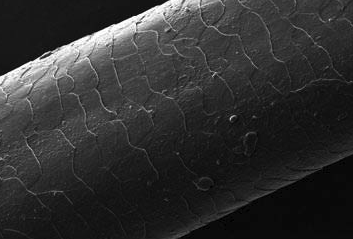

Horsehair is the most traditional and effective material, but we now have the technology to make bow hair out of other things. A company called  The other myth about rehairs is that horsehair gets worn out when the little “hooks” on it start to get dull. However, horsehair analyzed under a microscope is completely smooth. There are no hooks, it is the friction created by the rosin that makes the sound. To prove this, try playing on a new bow that has no rosin and see if you can make a sound!

The other myth about rehairs is that horsehair gets worn out when the little “hooks” on it start to get dull. However, horsehair analyzed under a microscope is completely smooth. There are no hooks, it is the friction created by the rosin that makes the sound. To prove this, try playing on a new bow that has no rosin and see if you can make a sound!

The material used for the tip of the bow is a complicated topic. The tip-plate is very important because it protects the wood of the tip from damage, so the material used must be strong. Historically, bowmakers used ivory. However, in 2016 the United States enacted a near-total ban on commercial trade of African elephant ivory. Other countries have similar laws. Bow tips fall under the very few exceptions, but only if the ivory was removed from the wild prior to 1976. Even so, traveling with such a bow requires a Musical Instrument Certificate from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, which must be paid for and is only valid for three years. Many musicians choose to avoid the hassle altogether and travel with different bows. Since new bows can no longer be made with ivory, bowmakers have turned to other materials. Mammoth ivory is a popular choice. (Note that it is illegal to use materials from an endangered species, but not illegal if the species is already extinct.) Other options include bone, faux ivory (a polymer), silver, or ebony. Some student bows may simply use plastic.

The material used for the tip of the bow is a complicated topic. The tip-plate is very important because it protects the wood of the tip from damage, so the material used must be strong. Historically, bowmakers used ivory. However, in 2016 the United States enacted a near-total ban on commercial trade of African elephant ivory. Other countries have similar laws. Bow tips fall under the very few exceptions, but only if the ivory was removed from the wild prior to 1976. Even so, traveling with such a bow requires a Musical Instrument Certificate from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, which must be paid for and is only valid for three years. Many musicians choose to avoid the hassle altogether and travel with different bows. Since new bows can no longer be made with ivory, bowmakers have turned to other materials. Mammoth ivory is a popular choice. (Note that it is illegal to use materials from an endangered species, but not illegal if the species is already extinct.) Other options include bone, faux ivory (a polymer), silver, or ebony. Some student bows may simply use plastic.