Martelé violin bow stroke explained

Martelé is an extremely important and useful bowing technique. It is another form of articulation that is different from staccato. Learning the different articulated bow strokes will not only teach you many things about technique, but also make your playing more musical.

What is Martelé bowing on the violin?

Martelé means “hammered” in French and refers to the specific technique of catching the string and creating a strong accent at the beginning of each note. People often think of it as a type of staccato, but it is really more similar to detaché. The strokes are long with a strong accent at the beginning. The bow is stopped after each note just long enough to prepare the next articulation.

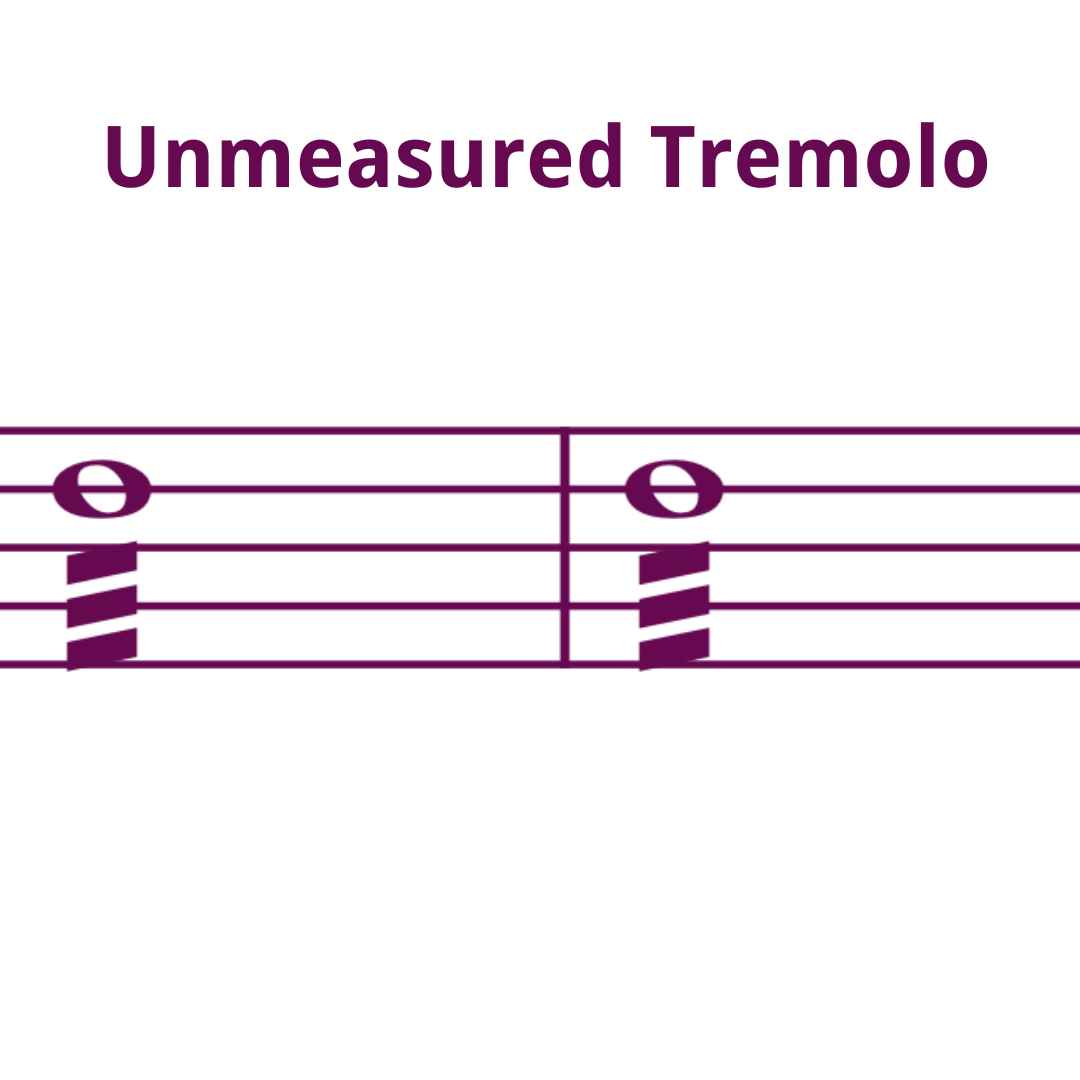

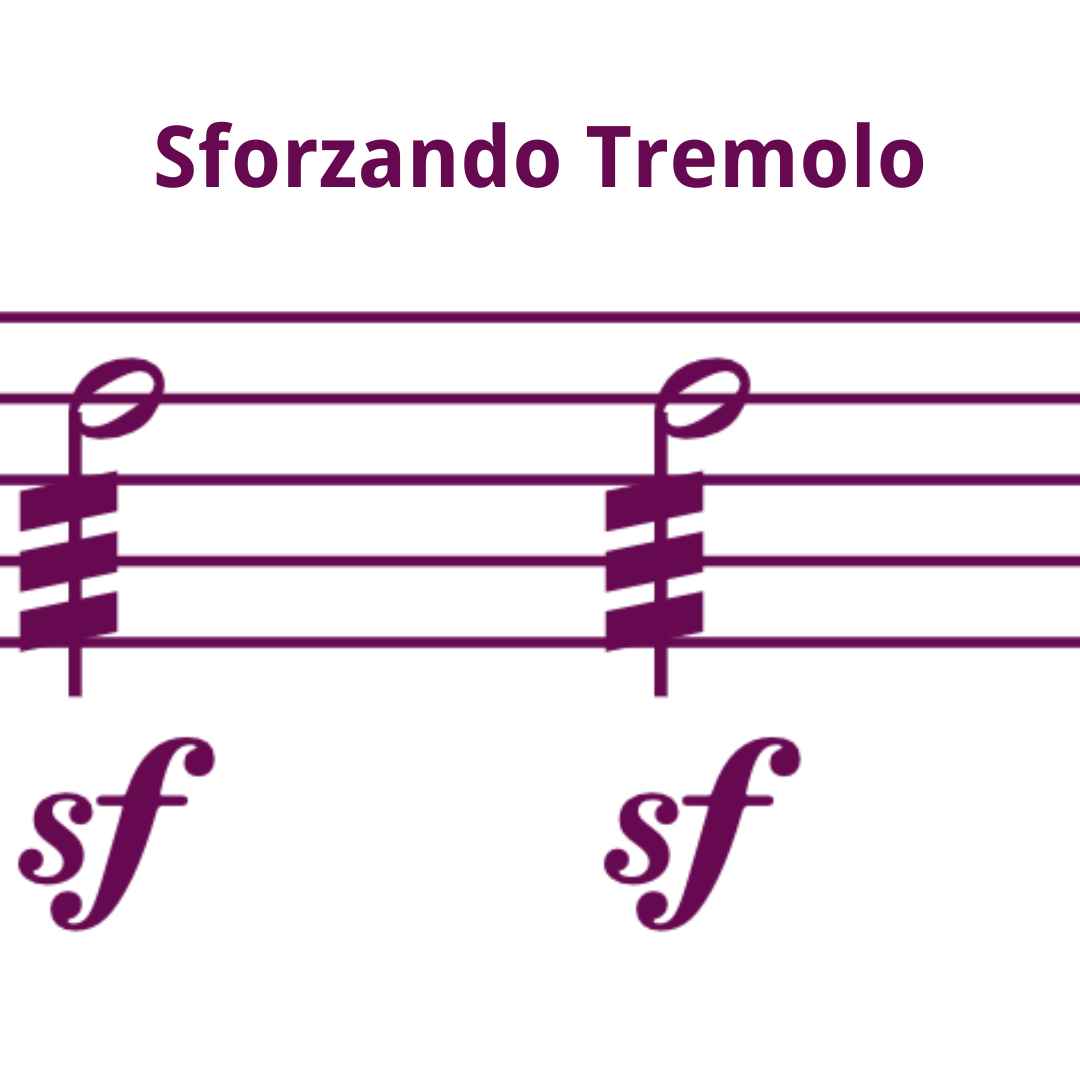

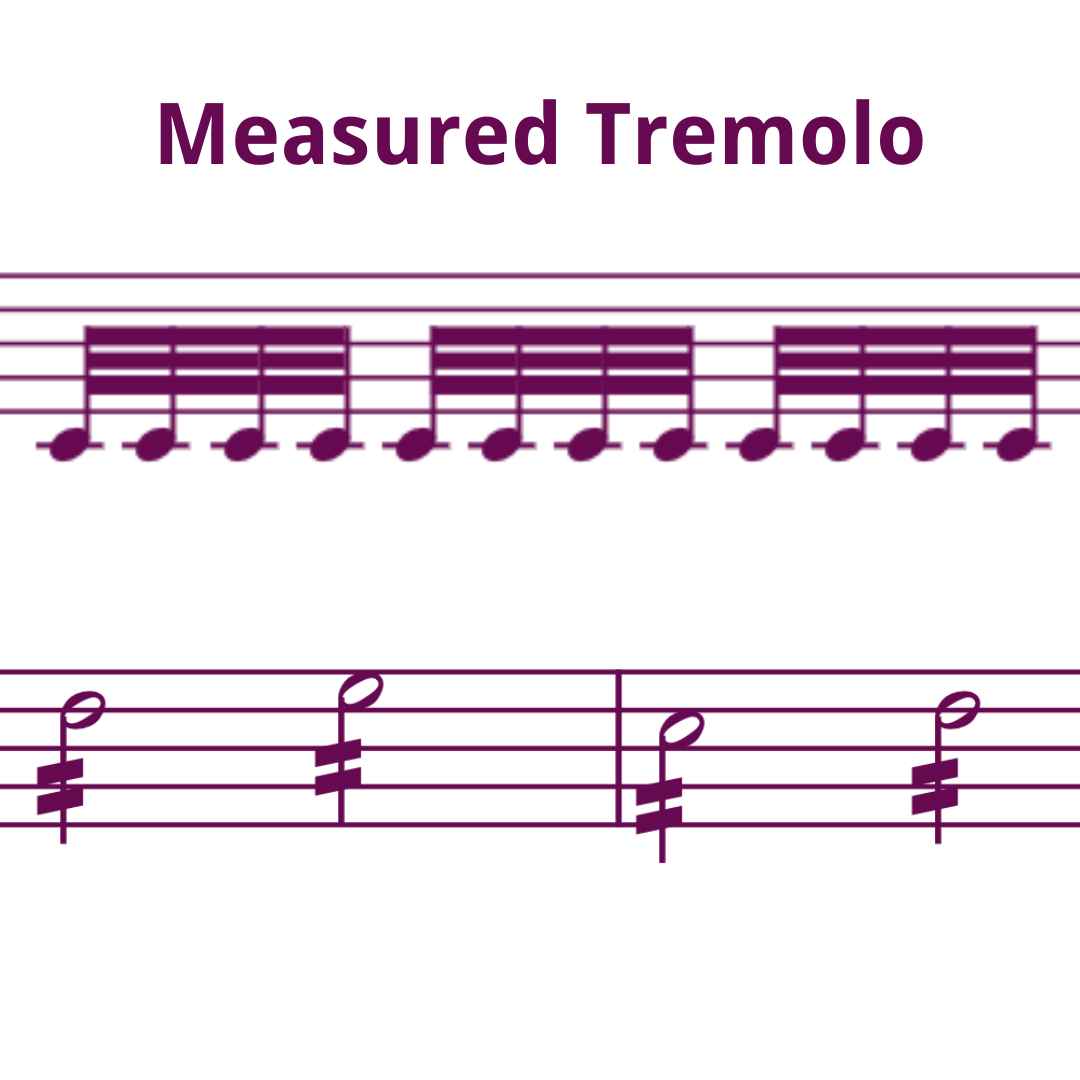

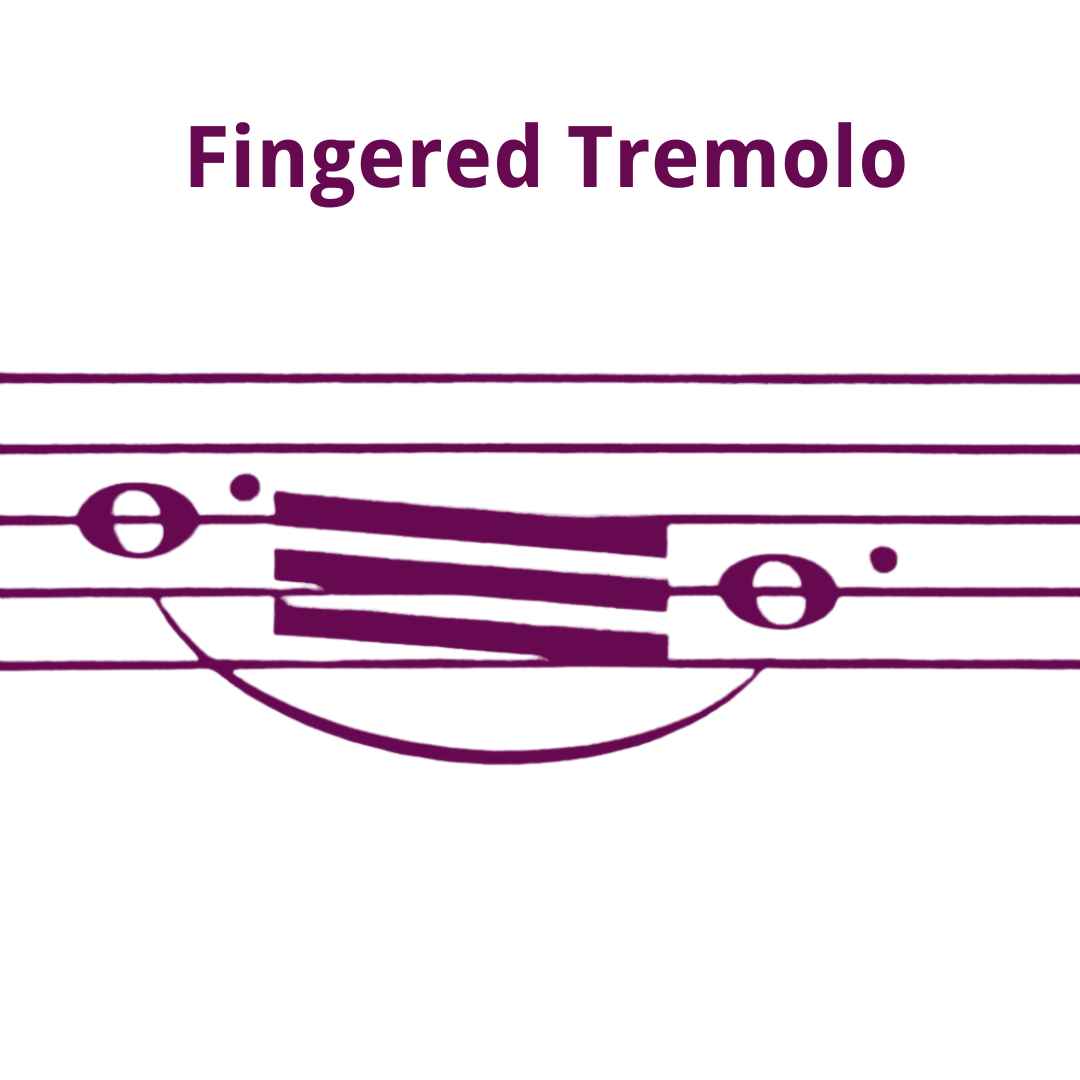

Martelé sheet music notation

In sheet music, martelé is notated with some sort of accent, usually the triangular wedge or a sforzando (sfz) marking. It is not only a dramatic articulation that adds excitement in pieces, but it is also a wonderful technical exercise that teaches sound production, bow division, relaxation, and control.

In sheet music, martelé is notated with some sort of accent, usually the triangular wedge or a sforzando (sfz) marking. It is not only a dramatic articulation that adds excitement in pieces, but it is also a wonderful technical exercise that teaches sound production, bow division, relaxation, and control.

How to Play and Practice Martelé on the Violin

Martelé is always started from the string, with firm, flat bow hair. The goal is to catch and release the hair, creating a strong and slightly percussive start to the note. It is very important not to press the entire time, but to release after the initial impulse and let the bow do the work, otherwise the sound will be strangled. It is aso important to hold the bow with rounded, relaxed fingers, because the pressure comes from the thumb and middle fingers. These fingers should be free to add and release pressure as needed. These fingers press slightly to initiate the impulse, then release as soon as the first “click” sounds so the rest of the note comes out smoothly.

The most difficult part of learning martelé is getting that initial contact to start the note. Put the bow firmly on the string at the frog, and use it to wiggle the string back and forth without actually making sound. Try this in all parts of the bow, experimenting with how much pressure is necessary to hold the string.

Now we will use martelé to play actually notes. Go back to the frog and wiggle the string again. Now, release the pressure and move the bow very quickly to the middle. (Martelé must be played with a fast bow stroke, but remember this does not mean a lot of pressure. “Poof” is a good word to describe martelé because the pressure is only at the beginning of the sound.) Use a mirror to be sure your bow hair stays straight and flat.

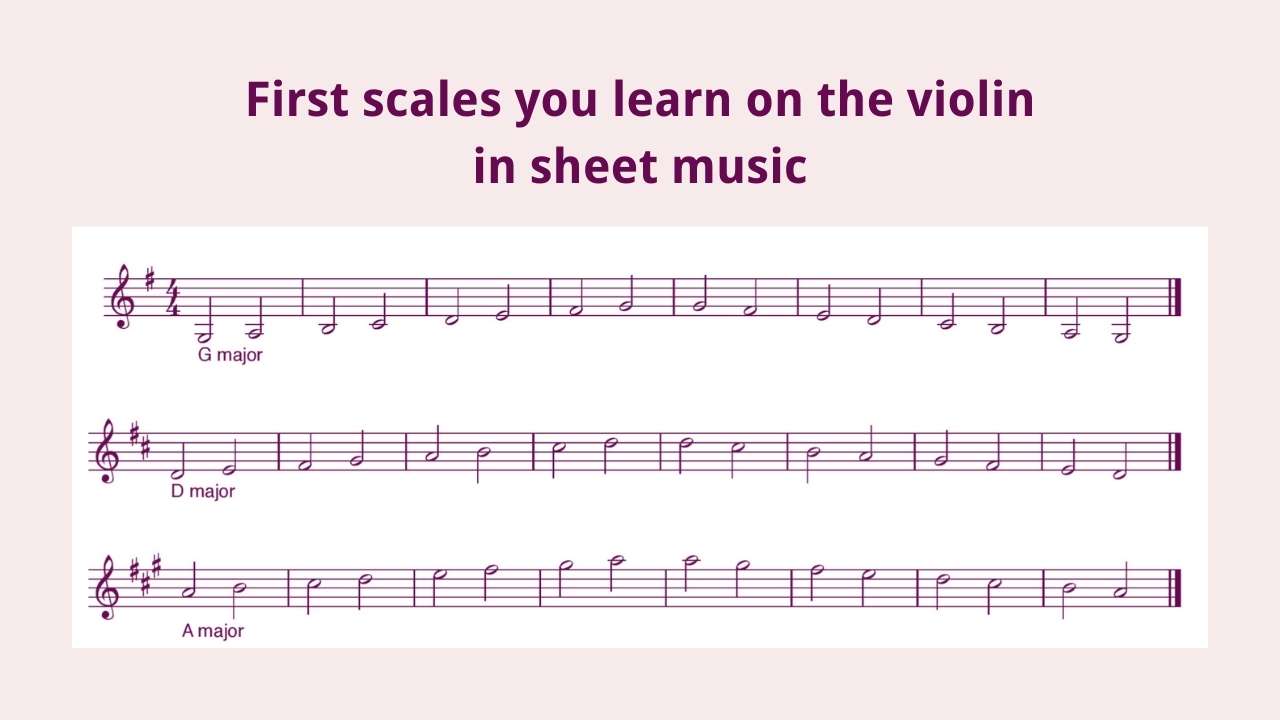

Practice martelé using scales (or, to think of it differently, practice scales using martelé). This helps incredibly with proper bow division (how much bow you use per note) intonation, and coordination. Pick a scale you are comfortable with in as many octaves as you can do. Start with two martelés per bow, dividing the bow evenly per note. Move up to three, then four, six, eight, and twelve, adjusting the length of each stroke. The trick here is keeping the bow strokes fast, but allowing space between the notes. The bow must stop completely between notes. Allow plenty of time at first to relax the right hand fingers throughout.

Martelé vs Staccato

It may be easy to confuse martelé and staccato. Martelé uses more bow and stronger accents than staccato does. The first movement of Vivaldi’s Violin Concerto in A Minor uses both martele and staccato. Can you tell the difference? Listen closely to the ending of the phrase at 0:25. In the Suzuki edition, the first two eighths are marked with a martele accent, and the second two with staccato dots. Making those articulations intentionally different creates variety and style.

Hi! I'm Zlata

Classical violinist helping you overcome technical struggles and play with feeling by improving your bow technique.

Improve your violin bowing technique with these lessons and articles:

Do you want to know every possible bowing technique on the violin? Watch this video with 102 violin bowing techniques.

The basis for all bowing techniques is to bow smoothly. This video lesson will help you with that.

A proper and relaxed violin bow hold will help a lot improving your bowing technique and sound. Read this article.

Take bowing technique lessons with Zlata

Join my Violin Bowing Bootcamp to build a great basic technique, make a beautiful sound and learn the most common bow strokes.

Join Bow like a Pro for personal guidance by Zlata and her teacher team combined with an extensive curriculum all things bowing.