History of the Violin Bow

The bow to a violin is like the voice to a singer

However, in the past violinists threw away bows as garbage when they were broken or old

Throughout the years the violin bow has changed a lot and was subject to many developments. This eventually led to the bow you’ll likely have in your house right now.

Sit back and let me take along the evolution of the violin bow:

Until 1600

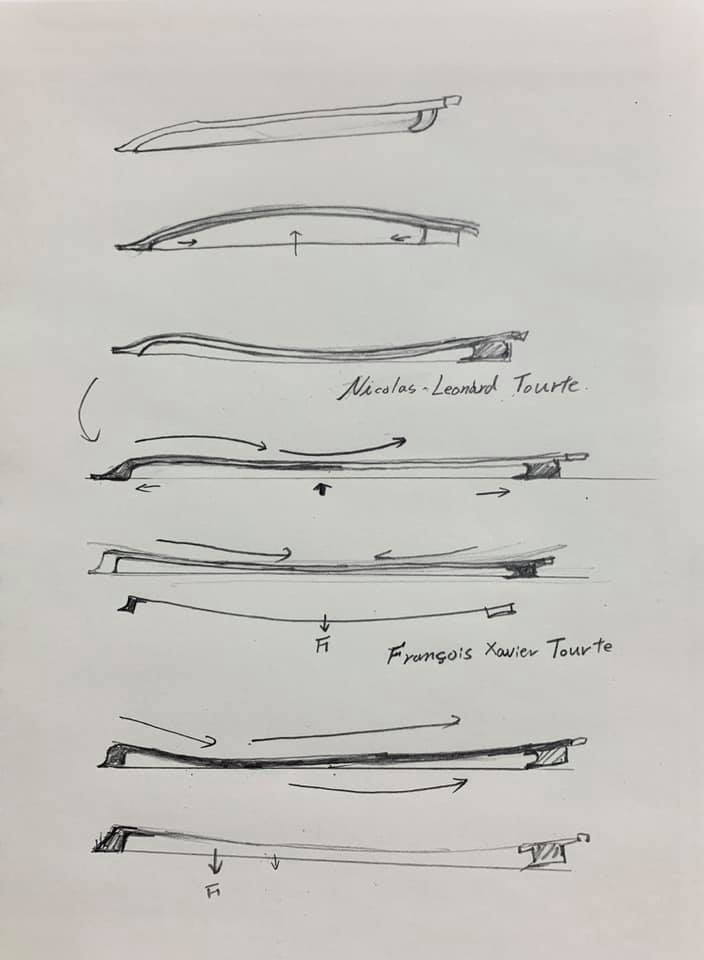

It is expected that bows of the first violins were equal to the bows of the predecessors of the violin: the rebec, the lira da braccio and the renaissance fiddle. The bows from this period had a characteristic shape. They were curved as a bow and arrow. Though it differed per stick how much the bow was curved, how the hair was secured and how long the bow was. In the period after this, bows became increasingly straight until they finally curved the other way like the modern bow we know today.

It is expected that bows of the first violins were equal to the bows of the predecessors of the violin: the rebec, the lira da braccio and the renaissance fiddle. The bows from this period had a characteristic shape. They were curved as a bow and arrow. Though it differed per stick how much the bow was curved, how the hair was secured and how long the bow was. In the period after this, bows became increasingly straight until they finally curved the other way like the modern bow we know today.

Unfortunately, little bows from this period were kept. It was much more usual to throw away a worn bow and replace it with a new one

The bows were developing very fast at this time, there was always something new and better. The fact that many bows were discarded in this period, tells us something about the worth the violin bow had in this period. The focus was on the violin, not on the bow. In addition, violinist were not thought of very highly, there were even many jokes about the violinists. They were often seen as useless privateers and not at all like artists.

Some bows of the period were very awkwardly and randomly put together, others were well balanced, relatively efficient and even elegant. Different frogs and tips were made to ensure that the stick was separated from the hair. Some bows, however, had no tip or frog.

Until the end of the seventeenth century it was not possible to tighten or loosen the hair of the bow. After this period the screw was invented and gave a whole new dimension to bows.

1600-1650

Bows from the early seventeenth century are rarer than violins from this period. The new bows that were made, were better suited to the changed musical and technical requirements. The older bows were unnecessary, so economically worthless. It didn’t seem worth it to store them and keep them in good condition. In addition, it was common to think of a bow as a disposable item and replace it with a new one if there was something wrong with it. It was hardly any more expensive to buy a new one instead of repairing the old one.

Bows from the early seventeenth century are rarer than violins from this period. The new bows that were made, were better suited to the changed musical and technical requirements. The older bows were unnecessary, so economically worthless. It didn’t seem worth it to store them and keep them in good condition. In addition, it was common to think of a bow as a disposable item and replace it with a new one if there was something wrong with it. It was hardly any more expensive to buy a new one instead of repairing the old one.

As you will read later in this article, the the perfected Tourte bow in 1780, made predecessors redundant

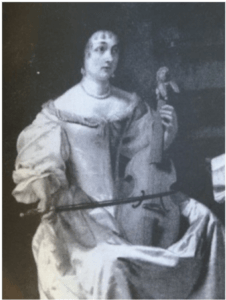

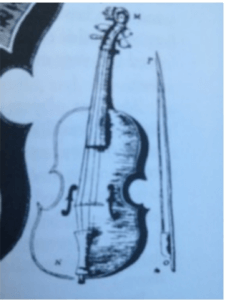

Because almost all bows in this period were thrown away, the information that we have about bows from the early seventeenth century, is based on drawings and paintings. Not so much on ‘real’ bows. As the creators of the drawings and paintings were no musicians, the question is how reliable these depictions are.

The bows in this period, certainly those for playing dance music, were relatively short. They were barely longer than the violin itself and slightly more than half of the length of the modern bow. The hair of these bows was thinner than that of our modern bows. The button at the beginning of the bow at the frog was a trim or a ‘ screw ‘ to tighten the hair. The difference is not noticeable on images, so we don’t really know if it was a trim or a screw. Presumably, the first bow with screw only appeared at the end of 17th century and the problem with tightening the hair was not yet resolved in this period.

Although the bows improved in weight, flexibility and stiffness, there was still little standardized and therefore bows differed very widely by the maker and country. Changes that took place in this time were generally that the bows became longer, the arch was flatter, there were better wood species selected (snakes wood was popular) and the stick was formed to combine strength and elasticity. These changes made sure that the balance was better, it was possible to make more subtle strokes, achieve a greater variation in tone and a larger range of dynamics and expression.

1650-1700

In this period, we see many different types of bows that were used for different purposes. In France, a relatively straight bow was used for dance music and opera. In Italy, a longer, straight or outward curved bow was used for the Sonata players. While in Germany a more curved bow was used and a lot of variation with the length of the bow. Presumably they were experimenting to be able to play strokes “with stops” like portato.

In this period, we see many different types of bows that were used for different purposes. In France, a relatively straight bow was used for dance music and opera. In Italy, a longer, straight or outward curved bow was used for the Sonata players. While in Germany a more curved bow was used and a lot of variation with the length of the bow. Presumably they were experimenting to be able to play strokes “with stops” like portato.

It is often thought that before the invention of the modern bow by Tourte, only boorish and clumsy bows were made. However, that’s very unlikely because builders like Stradivari, Stainer and Amati already paid so much attention to optimizing the sound of the violin.

We cannot longer assume that the bow was seen as irrelevant in this period. Stradivari even probably made a matching bow to one of his instruments from pernambuc wood. This is a type of wood that was previously not very common for making bows. Most bows were made out of ‘snake wood’. This bow is lighter and shorter than the modern Tourte bow, so it has less ‘ momentum ‘, but it has a similar quality of balance and response. The interesting thing is that modern violinists can play certain bowing techniques more easily with a Stradivari-like old bow instead of with a modern Tourte bow. This applies not only to music of that time, but also for example in Viotti, Beethoven or Mendelssohn.

At the end of the seventeenth century a movable frog was developed. An important development in the history of the bow. For example, the Stradivari bow that we mentioned earlier had one of them. This meant that the tension of the hair could be arranged. The bows that were developed at this time were not always shorter than the modern bow. Bow makers experimented a lot with the length of the bow. They even made some bows that were longer than the modern bow.

1700-1797

The historians tend to describe all the bows before the Tourte bows as boorish and simple, but we can recollect from the remaining images that the bows were actually very well developed.

The historians tend to describe all the bows before the Tourte bows as boorish and simple, but we can recollect from the remaining images that the bows were actually very well developed.

Despite that bows were made with a very good quality, there was no standard for the length and the properties of bows. It’s long been thought that the bows were made randomly, but since the violin making was already very developed, it is unlikely that the bows, which are very important for the sound and playing, weren’t made with knowledge and a certain precision.

In the beginning of the 18th century the bow developed even faster the violin itself

In the beginning of this century there was still a distinction between the previously described Italian bow (long and meant for playing Sonata’s) and the French bow (short and intended for dance music). This changed, however, from 1720, because of the creation of a Sonata school for French composers and players. The bow became straighter and longer and it looked very elegant. Some bows already show a preparation on the bending the other way (inward rather than outward), like the Tourte bow. The point of the bow began showing characteristics of the modern bow compared to the ‘ fluted ‘ Baroque bow in which we see the bow slowly descending. The German bows, however, were still bent outward. These bows were still not suitable for three-or four-tone chords.

Unfortunately, there are no bows preserved by Johann Sebastian Bach, so it’s a mystery what bow he used to carry out his violin Partitas, in which he uses many chords.

All developments that the bow had undergone so far, were already pointing to the development of the modern bow. These developments eventually came into being because of changing musical requirements and therefore the changing needs of violinists.

Eventually it was Francois Tourte, who used the experiments of other bow makers to create one standard bow design

He added all previous experiments together, optimized the design and also optimized the process of manufacturing. This bow became the standard for future bows to this day. This standard was even more of a determining factor than that Bett’s violin form of the Stradivari violin was for the violin building (there are still several violins built to the Guarneri model).

Tourte standardized the length and shape of violin, viola and cello bows and determined the form, the amount of hair, the material (pernambuco wood) and the way the bow was made. Tourte worked together with the violinist Viotti. It is striking that the equilibrium point of the Tourte bow is relatively high compared to its predecessors. Tourte made about 5000 bows in his life that through his great success were soon copied by many other bow makers.

FREE Violin Scale Book

Sensational Scales is a 85 page violin scale book that goes from simple beginner scales with finger charts all the way to all three octave scales and arpeggios

1797 – Now

In 1797 the English engineer Henry Maudslay applied for a patent on the first efficient screw-cutting lathe. Until then screws were difficult to make and really expensive which is why, until about 1800, only rich people could afford a bow with a screw while most musicians were using bows with clip in frogs. The wooden bows that are still widely used today stem from a time when pure gut strings with no windings were played. The first steel strings were made at the end of the 19th Century, when metal windings became available which allowed to play much more powerful. They became necessary because concerts were no longer played in the small halls of the nobility but in the new large public halls that were being built in the western world at the time. Steel strings became possible only with the technological advances at the end of the 19th Century high tensile steel wires became available.

Tourte and his followers designed the standard modern bow to match the strings that were being used during the 19th Century, which were predominantly pure gut strings. Metal windings were too expensive until about 1900. By then electricity became the big thing and copper wire was mass produced for cables. This copper wire was then used for winding the lower strings to give them more punch. At the same time the quality of steel improved to the point where thin wires could be made strong enough to be used as violin E-strings. (It was also the time that the grand piano was developed around the new “piano wire”.)

These new strings were much heavier than gut strings and allowed a much stronger technique. While pure gut violin strings can stand a force of only 2 Newton (200 grams), metal wound strings can take about 3 Newton. But that was not what the Tourte bows were designed for.

Since then players have had to develop a somewhat awkward and difficult technique to work with this uneven match of strong strings and soft bows.

All through the 19th and 20th centuries great efforts were made to develop a stronger bow. Vuillaume developed a metal tube bow of wich his workshop made and sold several thousand pieces and was also the preferred bow of Nicolo Paganini (see picture). This and later metal bows proved to be too fragile because the walls were only paper-thin.

All through the 19th and 20th centuries great efforts were made to develop a stronger bow. Vuillaume developed a metal tube bow of wich his workshop made and sold several thousand pieces and was also the preferred bow of Nicolo Paganini (see picture). This and later metal bows proved to be too fragile because the walls were only paper-thin.

When Bernd Müsing began to look into this problem, it was clear that only a tube made from high-density carbon fiber could provide significant improvements over pernambuco. Other simpler carbon bows did not offer the right elasticity and had too much high frequency damping, drawing a dull sound lacking badly in overtones. A violin bow with a clip in frog like those used until the early 19th Century weighs only about 40 grams. Its agility allows Bach and Mozart to be played with the appropriate delicacy. The heavy romantic Tourte bows ended up with a weight of about 60 grams. We found the ideal weight that allows a violinist to play the entire repertoire properly to be half way between the two extremes, at around 50 grams.

Most people think of wood as an especially resonant material ideal for making violin bows – which it isn’t

It was the only light construction material available during the time that stringed instruments were developed.

Carbon fiber components can have much better resonance characteristics than wooden parts – if designed and made properly

The vast majority of wooden bows that were made are long lost through wear and fatigue. Sweat degrades the wood, the screw wears the bore from the inside, metal strings leave dents in the shaft. Worst of all, the continuous vibrations of the stick wear out the material so that sooner or later the stick fails, usually at the thinnest part directly behind the head.

Hi! I'm Zlata

Let me help you find a great bow for your violin, so you can improve your bowing technique and sound quality:

How a good quality bow can cure the fatigue and pain in your shoulder, arm and hand

Within the first year of Arcus bow production several musicians discovered that the Arcus bows apparently solved ergonomic problems including pain and fatigue in the thump, wrist, elbow and shoulder of the bow arm.

They found that the 50 Hz low frequency vibration of traditional bows are the cause of these problems. The reduced weight and increased stiffness of the Arcus sticks shift their fundamental resonance to 100 Hz (one octave higher), which seems to be well outside the dangerous frequency range.

My arm is not even tired after an eight hour orchestra day with my Arcus S9 violin bow

Expand your possibilites in sound, musical expression and interpretation

Most players who own an Arcus bow play it exclusively. The most important reason is probably that no conventional bows offer the same variability in sound and technique.

An Arcus enhances the freedom of interpretation and allows to play with increased precision and clarity. The articulation is crisp and clear. Perfect intonation in the upper registers is also more easy to achieve due to the clear and transparent sound they draw. The sound of the lower strings comes out more melodic.

Arpeggio and fast string crossings are easier to execute because the bows are lighter and perfectly balanced (you’ll feel like your cheating!). Even col-legno doesn’t need to trouble you any further, as the stick’s surface is harder than the metal winding of the strings. Finally you can play at full power without damaging the stick or the bow hair.

I would like to collaborate with you.

Sure, send me your ideas to info@violinlounge.com. Looking forward to your message, Aldous!

For those who wonder what the resource is of this article… I got most information from ‘The history of violin playing from it’s origins to 1761’ by David D Boyden and various other violin methodology books.

Thank you very much and gratitude has been very informative and interesting and very useful and helpful once again thank you very very much a million times a million times over in gratitude and appreciation you everybody to take care and have the best of luck and best wishes thank you very much again

You’re most welcome, Robert!

I found this to be very interesting reading and I thank you for the time you put into this for us. 🙂

A very good article indeed.

It makes me think that I would like to contribte from the point of view of someone who has seen and re-haired a vast quantity of bows, of many different kinds.

One thing that puzzles me is that many violin, viola, cello and double-bass players do not care enough to maintain their bows in a good playing condition…

Still that is why I am on hand to redress that sad fact.

If you wish me to contribute to any further article, I would be happy to pass on my opinion and the little knowledge I have gained over the last 40 years in the trade.

Sicerely,

Francois Bignon

Moseley Violins

Dear Francois, thank you for the kind offer to write an article. I’d love you to share your expertise as a bow maker. I also see students tighten their bows very much and use too much rosin. As I’m a player and teacher, I’d love to have someone as you write it from your perspective.

Best regards, Zlata

PS: I’m sending you an e-mail to talk further.

Apart from the concertina family ,bowed instruments are unique generating and sustaining tone in both dire

ctions of movement.

Hi, would you mind sharing some of your sources for further reading on early bows (particularly early 17th century)?

This book by Boyden might give further insight and at least also some resources to dive in further.

Please do not distort history in order to sell carbon fiber bows. A wooden bow being worn out because of the “continuous vibration of the stick” is completely false.Yes, it is true that wooden bows have a certain amount of wear and tear but so do violins and I certainly would not want to play on a carbon fiber bow or violin.