Shifting vs Glissando vs Portamento on the Violin: What’s the difference?

Learn four different ways of changing positions on the violin

So, you started your violin journey a while ago now. You’ve learned several pieces, scales, and you are comfortable with different positions (at least first and third). Perhaps you’ve even started working on vibrato. Now that you have these basics down, why not spice things up a bit? For example, why not learn how to add various kinds of expression to your shifts? In this article we will discuss the best way to execute regular shifts, but also ways to add juicy stylistic flair, also known as glissando and portamento.

Regular Shifts

Regular shifting is the most basic form of changing positions on the violin. When shifting, the “old finger” lifts off the string slightly but not completely. By sliding lightly along the string the old finger guides the hand to the new position. Lifting the finger just enough so that it does not make a sound disguises the shift. Many students disregard guide fingers, which makes their shifting insecure and inconsistent.

A good example of clean shifting with guide fingers is found in the opening of the Mendelssohn concerto. In the second measure of the solo part, Hilary Hahn shifts from second to fourth position by keeping first finger on the string during the shift. You may want to watch in slow motion to catch this!

Jump Shifts

If you have a big shift of five positions or more, there is not always time to slide on the guide finger, especially if there is a string crossing involved. Any time all the fingers leave the string (intentionally!) during the shift, it is called a jump shift. Jump shifts should be practiced very slowly and methodically because it is challenging to land in the same spot every time. Additionally, you can use visual/physical landmarks such as where your left hand is in relation to the edge of the violin to remember what position you’re going to.

Beethoven’s beautiful Romance No. 2 in F Major has some examples of jump shifts. At one point, the melody goes from an open G straight to a high F in 5th position on the E string—a jump of three octaves! In this recording, Capuçon is already in third position on the D string (in order to vibrate open G) then he lifts all his fingers, changes to E string and only has to go up two positions. Again, watch in slow motion to really see the shift.

Click here to watch the video example.

Glissando vs. Portamento

The stylistic components of violin playing have changed greatly over the years. A hundred years ago, sliding audibly between shifts was popular because it sounded sweet and emotional. This heart-on-your-sleeve technique gave every violinist a unique sound. Today, playing cleanly is more encouraged, but it is important to know how to use slides tastefully. There are two main types which often get confused: glissandi and portamenti. Both words describe sliding between two notes, but in different ways.

In sheet music, a glissando is marked by a straight line between two notes. In solo music adding a glissando is often a stylistic choice and may not be marked at all. Glissandi are found in both solo and orchestral music. Below is a recording of Sensemaya by Ravueltas, a dramatic modern piece based on a poem about killing a snake. At the climax, watch how the first violins are sliding up and down the G string, adding color, texture, and energy to the orchestra.

Portamento means “to carry”, and is shorter and more subtle than a glissando. 20th-century violinists added portamenti to their shifts all the time. There are two basic ways to do portamenti. In the first, you slide on the old finger and place the new finger only after reaching the new position. In the second way, you change fingers half-way through the slide. For example, say you are sliding on the A string from 1st finger B (first position) to second finger E (third position). Start the slide on the first finger, then put second finger down and complete the slide into the E. It will help if you use the flat part of the fingers instead of trying to balance on the tip.

FREE Violin Scale Book

Sensational Scales is a 85 page violin scale book that goes from simple beginner scales with finger charts all the way to all three octave scales and arpeggios

Hi! I'm Zlata

Classical violinist helping you overcome technical struggles and play with feeling by improving your bow technique.

Going back to Hilary Hahn’s Mendelssohn, she uses this second type of portamento in the opening of the second movement. At the end of the solo part’s first measure she shifts from B to A, putting the third finger down half-way through the slide.

The differences between glissandi and portamenti can be subtle, but a skilled player knows what is tasteful and appropriate. Do you have a favorite violin shifting technique? What about a favorite early 20th-century violinist? Please share any thoughts and tips below!

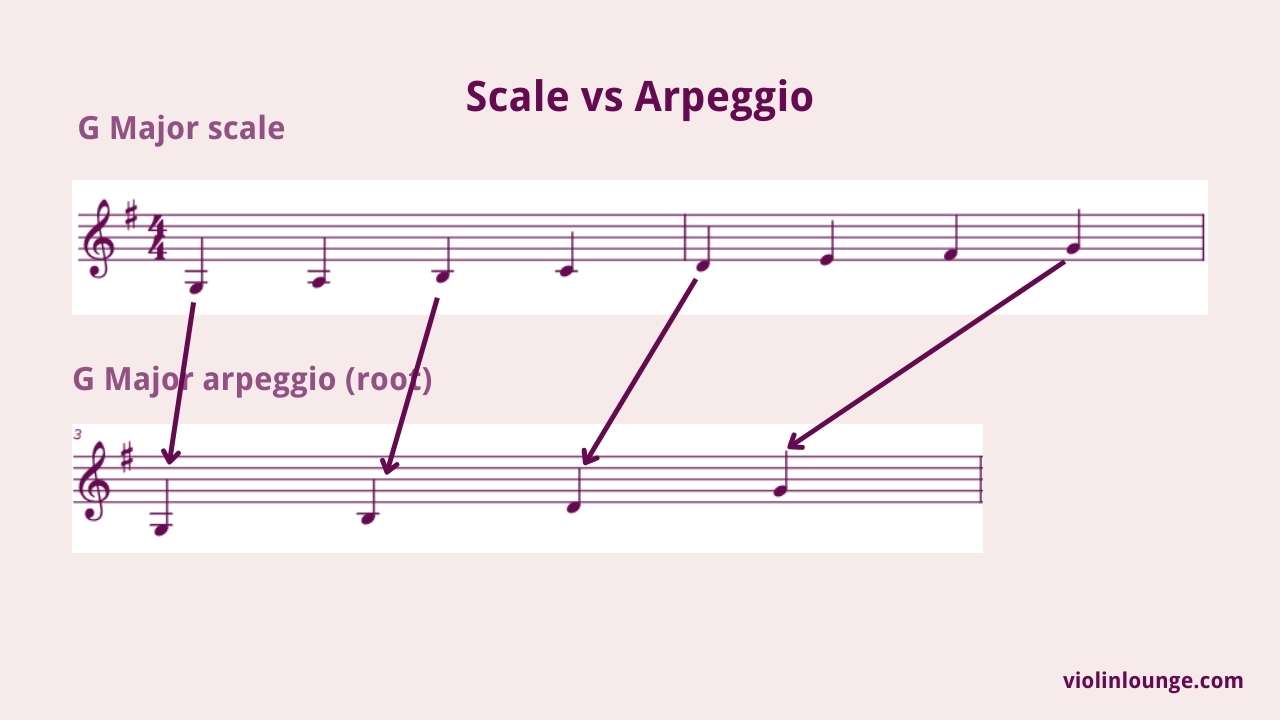

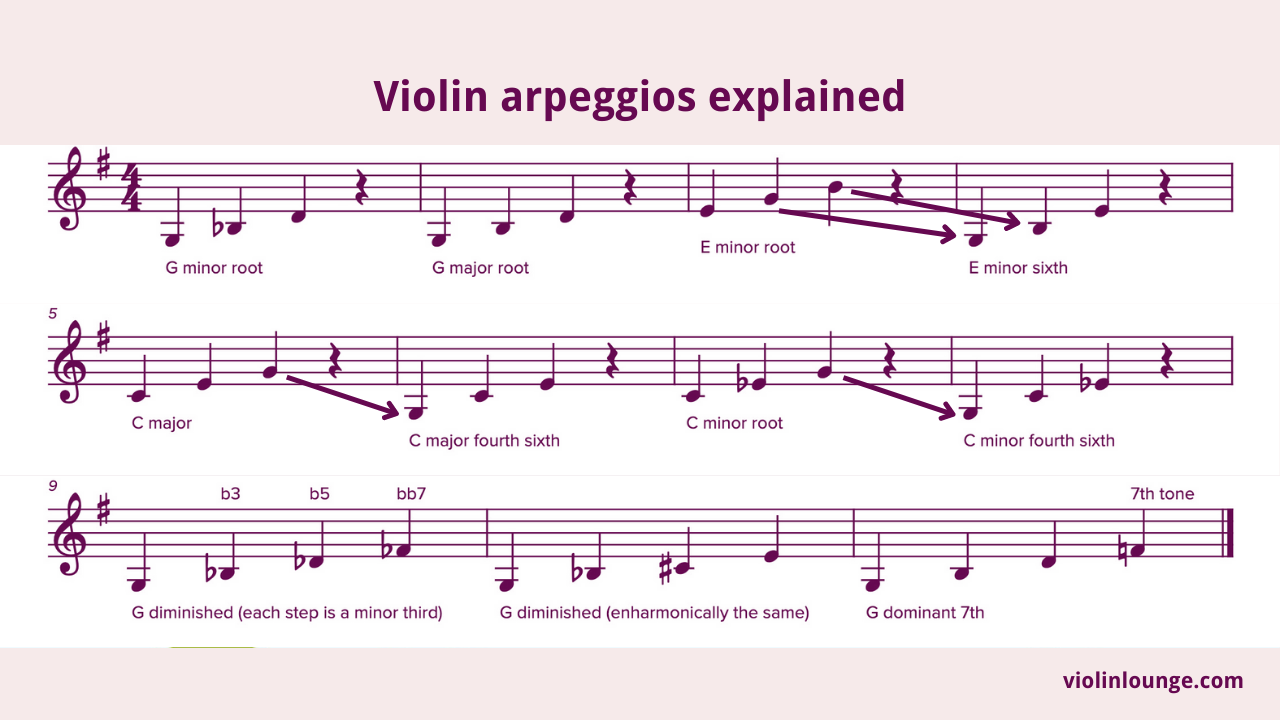

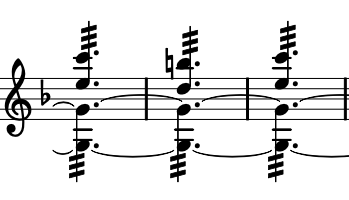

In a chord the notes are placed above each other in the sheet music and they are played at the same time. In an arpeggio the notes are played one by one starting on the lowest note. Sometimes in sheet music arpeggios are written like chords, but with a vertical wave next to them or with a tremolo notation like in the picture.

In a chord the notes are placed above each other in the sheet music and they are played at the same time. In an arpeggio the notes are played one by one starting on the lowest note. Sometimes in sheet music arpeggios are written like chords, but with a vertical wave next to them or with a tremolo notation like in the picture.