Violin Second Position – all notes, finger chart and exercises

Second Position: no man’s land on the violin

The second position can feel like no man’s land on the violin. In the first position you have the reference point of the nut and the peg pox. In the third position and higher you have the reference points of the soundbox. While the highest positions are known to be most difficult, it’s actually the second position that a lot of players struggle with to play in tune.

Don’t worry! In this article I will show you exactly where to find the notes in the second position on the violin, the sheet music and how to practice them.

Especially in an orchestra the second position is very useful to decide on handy fingerings. It really pays off to learn. As a student said: upon having an aha moment when discovering the conveniences of second position proficiency, “Wow, it gives me all the shortcuts, like right click on the mouse.”

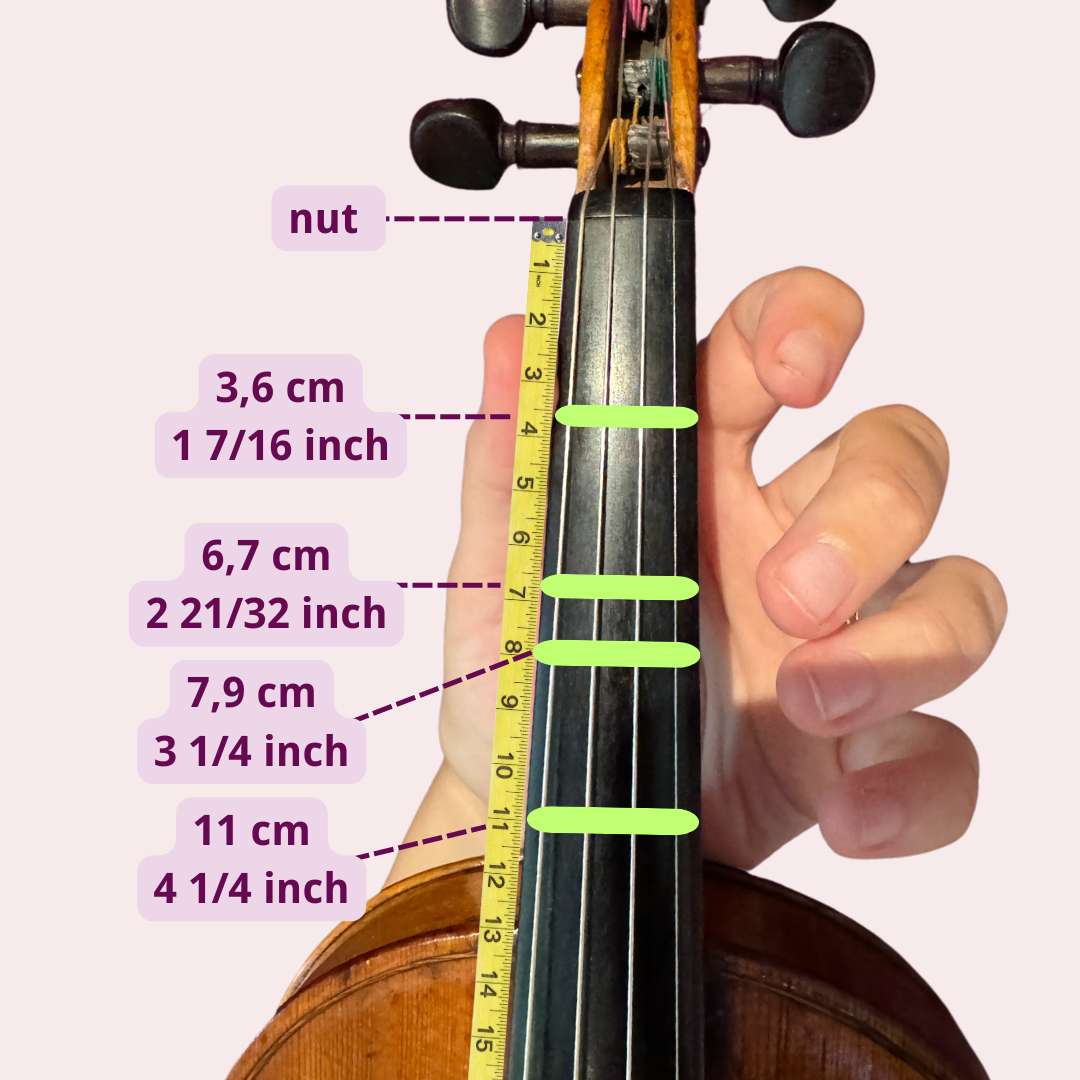

Finding the second position on the violin

Second position starts where second finger would be in first position. For example, on the A string, second finger goes on C in first position. In second position, you will start on C (or C#, both count.)

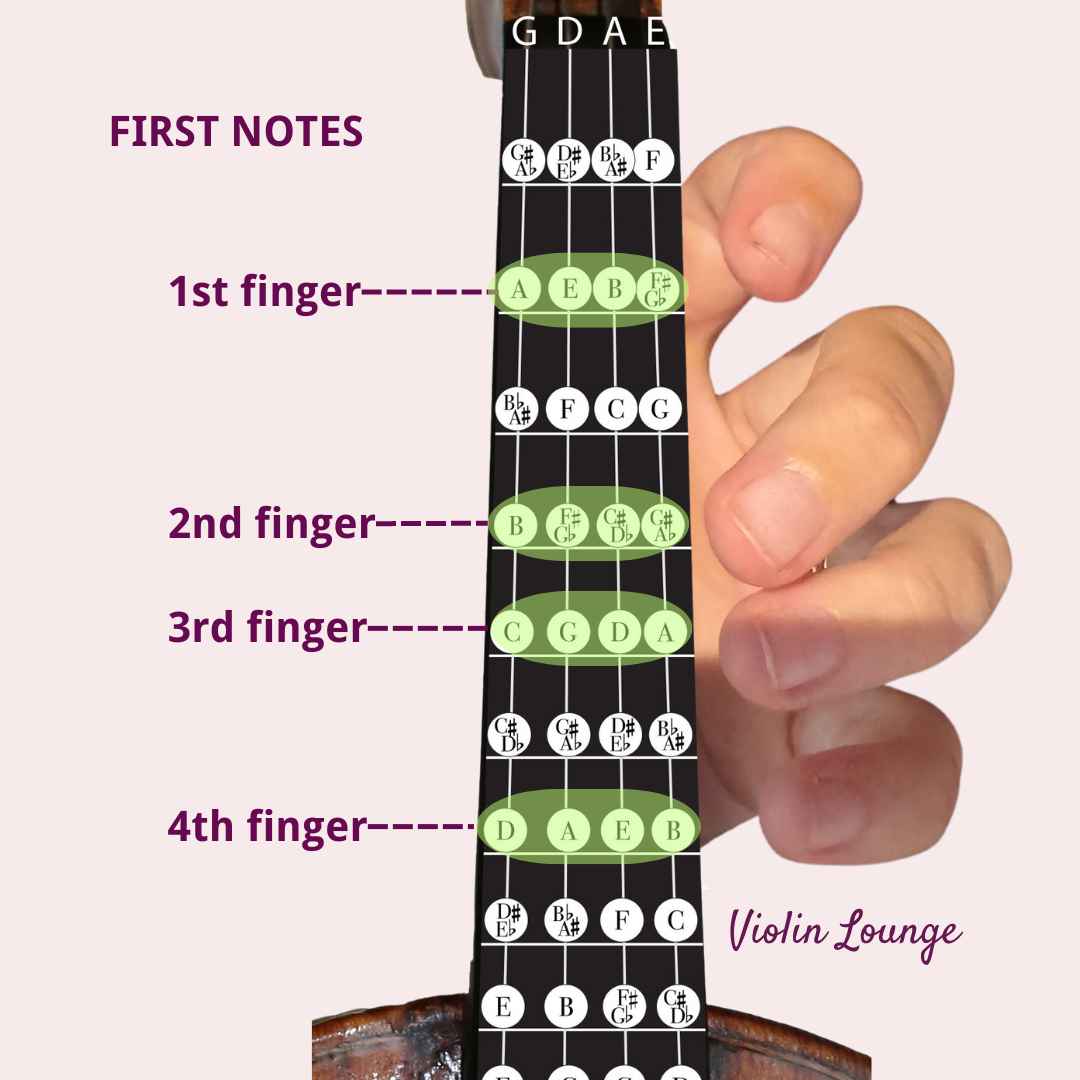

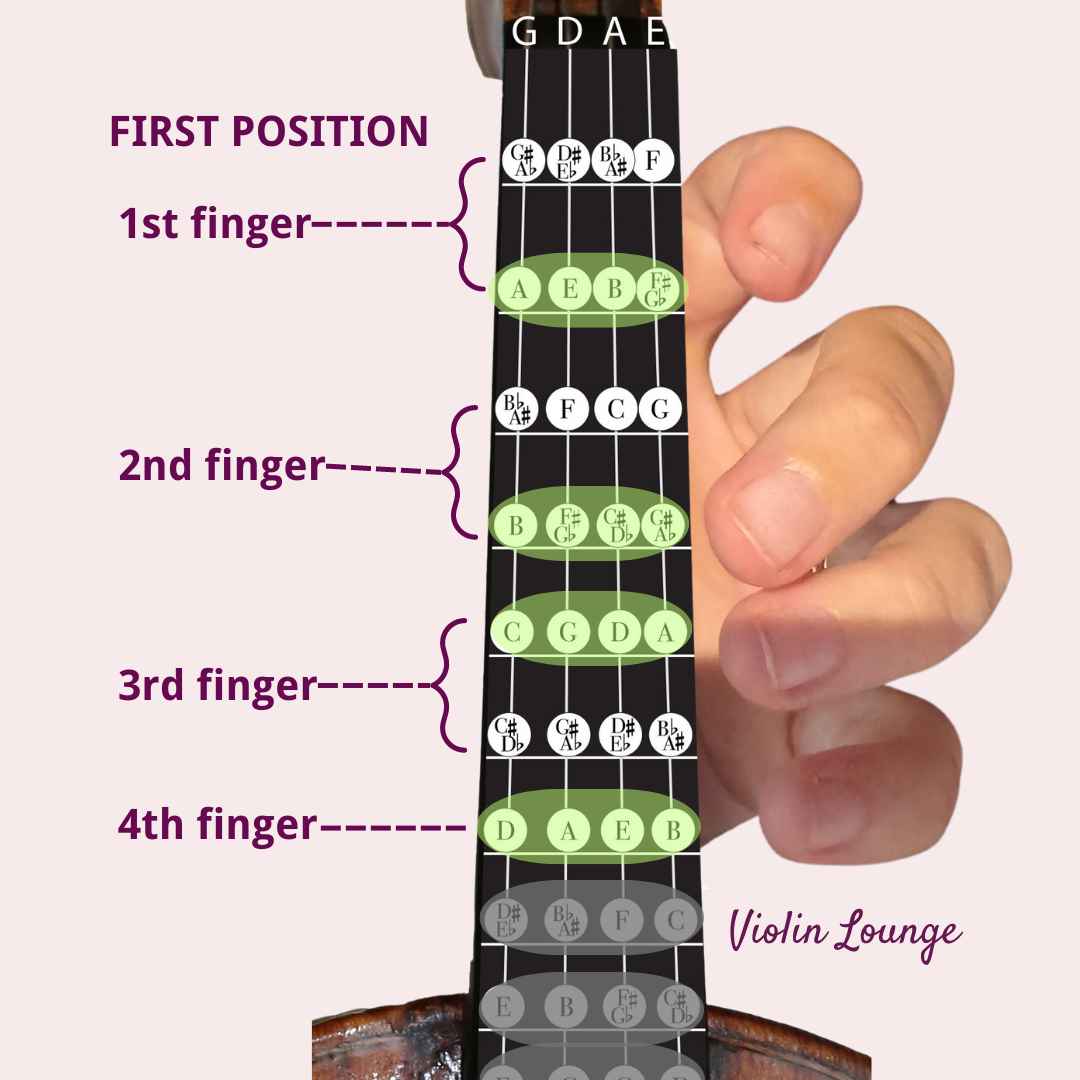

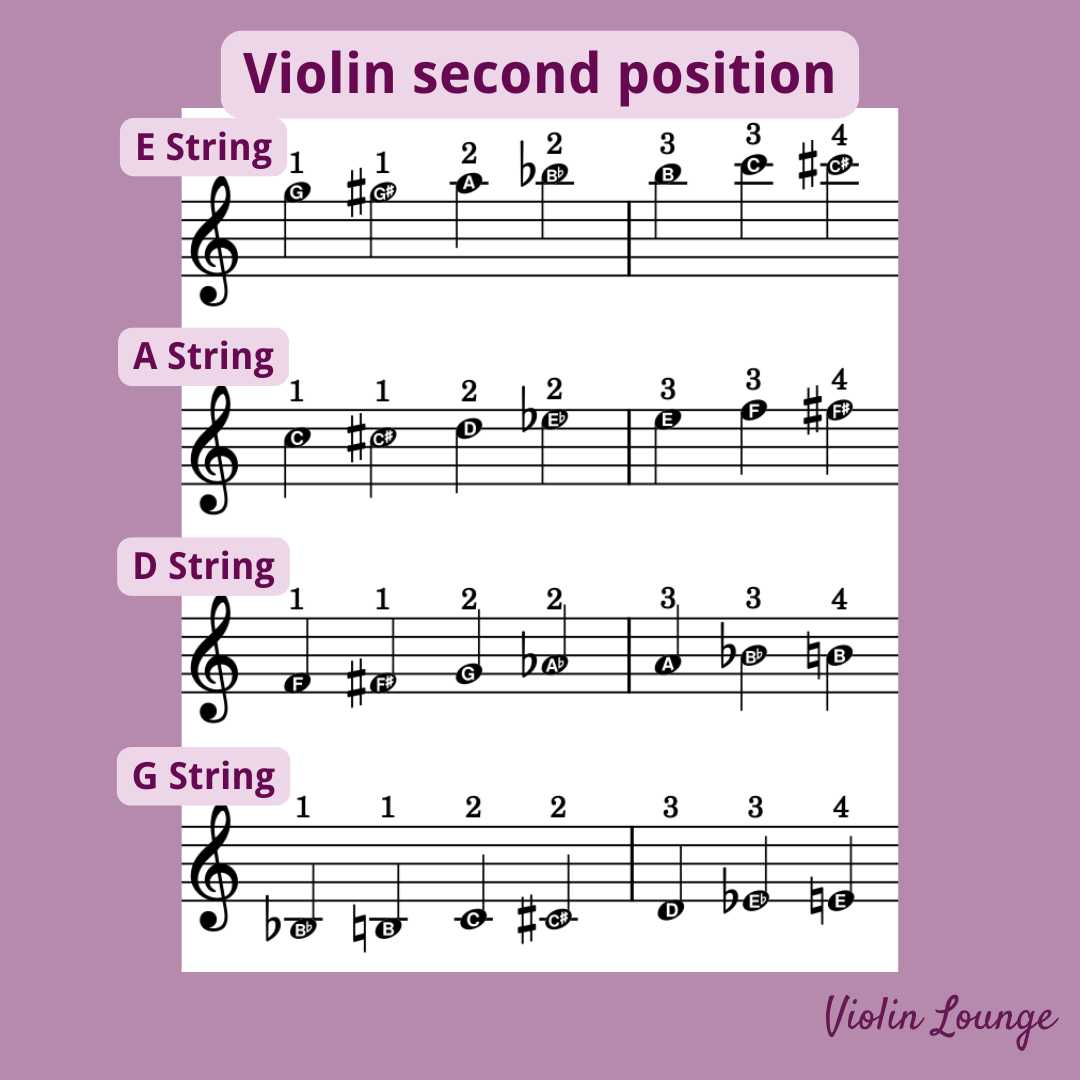

Finger chart of second position

This chart will help you visualize and understand the second position and it’s left hand posture:

Notes in Second Position

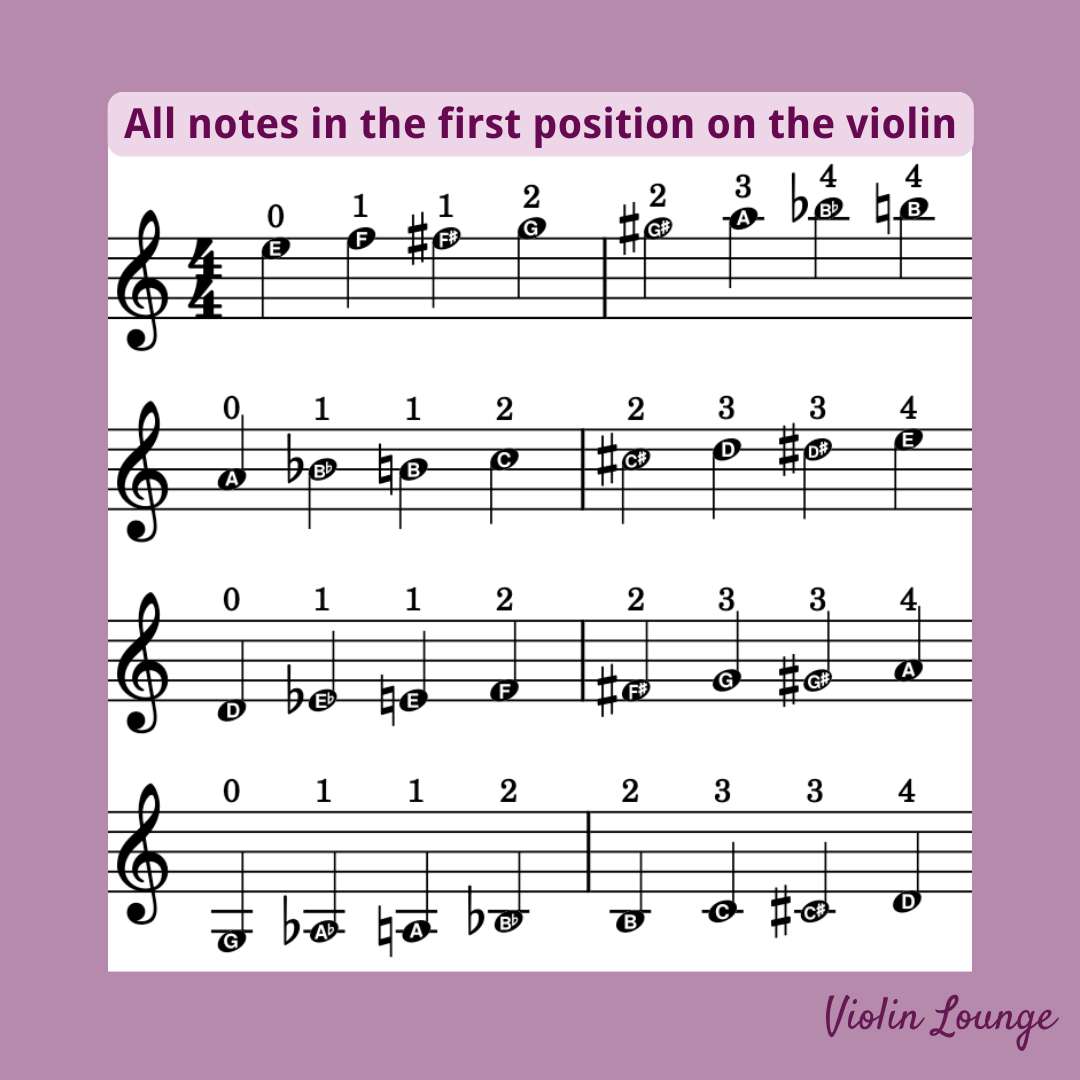

The full chromatic range of notes you can play in second position are as follows:

G string: A#/B♭, B, C, C#/D♭, D, D#/E♭, E

D string: F, F#/G♭, G, G#/A♭, A, A#/B♭, B

A string: C, C#/D♭, D, D#/E♭, E, F, F#/G♭

E string: G, G#/A♭, A, A#/B♭, B, C, C#/D♭

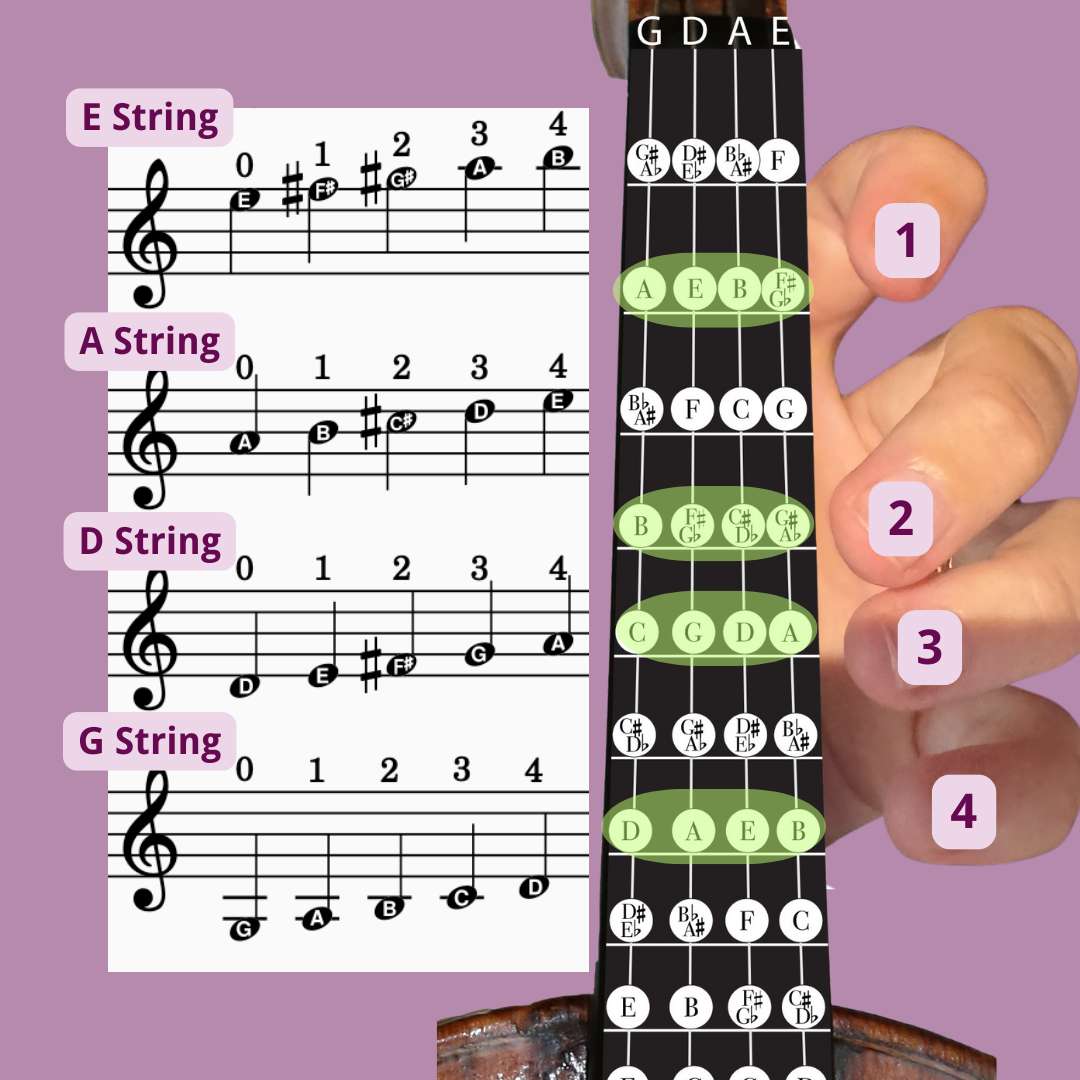

Sheet music of the second position

This is what the second position notes look like in violin sheet music. I’ve chosen between notes that are enharmonically the same. Of course if a F# is possible, a Gb is possible too (also see the finger chart above).

How will you know when to play in second position?

There will usually be a fingering marked in the music at least for where the shift to second position occurs. Beginning pieces may have the second position fingerings marked for the entire passage. For example, if you see an A in the middle of the staff but there is a three written over it, that means it is in second position. Violin fingerings will always try to minimize shifting, so stay in second position for as long as you can if it helps avoid string crossings or awkward trills.

Exercises and pieces in second position

Second position is less common than first, third, or fifth. It’s used for short passages that would be too uncomfortable or clumsy in first or third positions. Thus there are not many pieces that have extended second position passages, but there are plenty of etudes and scale exercises that focus on strengthening second position. Here are a few good places to start:

- The School of Violin Technics, Book 1 no 8 and 9 (exercises in the first and second position) by Sevcik

- Introducing the Positions Vol. 2 by Harvey S. Whistler

- 20 Etudes by Hans Sitt

- 42 Etudes by Rudolphe Kreutzer (specifically, play Etude No. 2 entirely in second position)

- Second and Fourth Position String Builder by Samuel Applebaum

- Allemande from Bach’s Partita for Solo Violin in D Minor (This relatively short piece contains several passages that are best in second position)

- Violin Concerto in C Major by Kabalevsky (great for practicing string crossings in second position and fast shifts)

Examples of Second Position

Here is an example of what second position looks like while playing. In this under tempo version of the Kabalevsky, you can clearly see her shift to first finger, second position on the A string after the first few measures. Notice how she stays in second position for as long as she can afterwards:

How to Learn Second Position

Second position intimidates many people, but it is not difficult to learn. Many teachers prefer that students learn third position first and then go back to second position. This is a good idea, but if you want or need to play second position, don’t worry whether you have learned third or not. Just make sure you are solid in first position as your basis before adding others.

I suggest learning the finger placement in second position before you practice shifting to it. Since it is a little higher up the fingerboard, the finger spacing will be a bit more narrow. Practice finding both low second position and high second position. In low second position, the first finger should be on B♭, F, C, or G (based on what string you are on). In high second, first finger is on B, F#, C#, or G#.

Initially, it might be a little tricky to understand the hand frames for second position. “Should I use low second position or high second position?” “Does third finger touch second finger or is there a space?” “What do I do for sharps and flats?” don’t panic! Just remember that for a half step, two fingers will always touch and for a whole step, there will always be a space.

Here are a few practice exercises to try:

- Start on first finger, second position on the A string (a C natural). Put second finger a half step up, touching, on C#. Alternate between the two notes to get used to the spacing. Then move second finger over to D and alternate. Keeping second finger down on D, put third finger on E♭. Alternate two and three. Move third up to E natural and alternate. Continue doing this pattern and try the other strings also until you are comfortable with all the half steps in second position.

- Here is a shifting exercise. Put first finger, first position on the A string (B natural). With you finger and hand gently leading, slowly slide your arm forward to second position, then back down. Continue the “siren”, keeping the finger in the string the whole time so you can clearly hear the shift. Later, you can lift the finger pressure slightly off the string (but still touching it) to make the shift silent. Tyr this shifting from every finger to its corresponding note in second position.

Note: For shifting, remember to let your left thumb be loose, and let your palm hand down towards the ground rather than gripping the fingerboard. Also be sure to shift your whole arm and hand, instead of just reaching one finger up. This creates tension and won’t help you create a good second position hand frame. Once you have routinely practiced second position, you will be amazed how useful and flexible it is!

Hi! I'm Zlata

Classical violinist helping you overcome technical struggles and play with feeling by improving your bow technique.

Learn to play in tune in the second position

The second position is a weak spot for many violin players, all while it can come in so handy when you’re proficient in it. For me it felt like no man’s land for many years and I always felt insecure and tried to avoid it.

It took exercises in the style of Paganini to get it solid for me and now I’m happy that I have the second position in my tool box.

Great exercises to get reliable intonation in the second position are left hand pizzicato exercises, drone scales, double stop arpeggios, shifting exercises. glissando scales, artificial harmonics and velocity exercises.

In my online membership Paganini’s Secret, there’s a whole module all about the second position which will improve your playing guaranteed. Check it out and register right here.